World Wide Web: what it is and how the global net works

For all of us, users of the Net and, more specifically, online professionals, March 12, 1989, should be remembered as a special day: on that date, in fact, Tim Berners-Lee first described how the World Wide Web, which would later become the main service of the Internet and the system for using most content hosted online, works. Let’s try to get a good understanding of what the WWW or World Wide Web is, how it works, and why it is different from the Internet.

What World Wide Web means and what it is

In fact, it is good to remember that World Wide Web does not mean the Internet, but is “only” a part of it (although the one that is probably the most substantial): with this acronym we refer precisely to what in Italian we call the Net, that is, the system that allows us to manage the large amount of online content, which precisely in 1989 was imagined as a tool to allow the approximately 17,000 scientists at CERN to store and share their scientific experiments.

Technically speaking, taking the definitions from the prestigious Encyclopedia Britannica, the World Wide Web or WWW, also nicknamed Web or Network, is the main information retrieval service of the Internet (the worldwide computer network). The Web offers users access to a wide range of content, via the deep web, the dark web, and the surface web, which is the most commonly accessed, connected via hypertext or hypermedia links, such as hyperlinks, which are electronic connections that link related information in order to allow a user easy access to it (i.e., links). Hypertext allows a user to select a word or phrase from the text and then access other documents that contain additional information related to that word or phrase. Hypermedia documents have links to images, sounds, animations and movies. The Web operates within the basic Internet client-server format; servers are computer programs that store and transmit documents to other computers on the network when requested, while clients are programs that request documents from a server when the user requests them. Browser software allows users to view retrieved documents, and special browsers and platforms such as Tor allow users to do so anonymously. A hypertext document with corresponding text and hyperlinks is written in HyperText Markup Language (HTML) and assigned an online address called a Uniform Resource Locator (URL).

The history of the WWW and the invention of Tim Berners-Lee

The daddy of this revolution is Tim Berners-Lee, a British scientist, who invented the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1989 while working at CERN in Geneva, a laboratory that serves more accurately as the hub and focal point of a vast community that includes more than 17,000 scientists from over 100 countries. In order to simplify and optimize the demand for automatic information sharing among scientists in universities and institutes around the world, it became necessary to devise and develop a reliable system for communication and transmission of data and information, and the basic idea of the WWW was precisely to merge the evolving technologies of computers, data networks, and hypertext into a powerful and easy-to-use global information system.

To be precise, in the paper on <strong>information management systems</strong> presented in March 1989 to his handlers at CERN in Geneva (using the computer that housed the first server in the history of links, namely a <strong>NeXT</strong> created by the company founded by Steve Jobs who had just left Apple), Berners-Lee called and called this system “MESH,” but as early as the following year the first web page with the three letters we know well today was published.

Tim Berners-Lee wrote the first proposal for the World Wide Web in March 1989 and his second proposal in May 1990; together with Belgian systems engineer Robert Cailliau, the latter was formalized as a management proposal in November 1990, and outlines the main concepts and important terms behind the Web. Indeed, the document describes a “hypertext project” called “WorldWideWeb” in which a “network” of “hypertext documents” could be viewed by “browsers.”

The first page with WWW

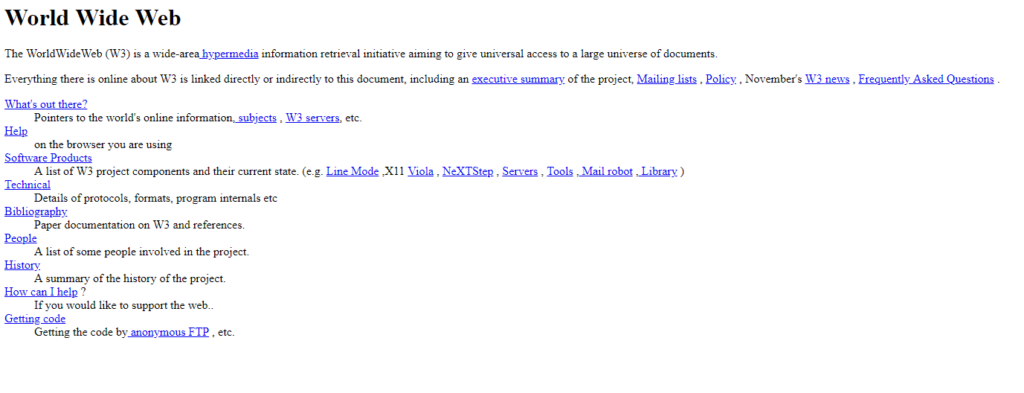

We also see this in the depiction above, which shows the first page where the expression WWW or World Wide Web appears.

It is a kind of primordial landing page, which is still active today and can be visited at the URL http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html, and basically provides a concise description of the project, which through a series of internal links (the usefulness of which was already understood then!) allows one to reach other related pages. In short, in 1990 the architecture of a site was similar to what it is today, and links were beginning to play a key role even in the pre-Google and pre-SEO era.

The design of the WWW quickly allowed easy access to existing information, with the first Web page linked to information useful to CERN scientists (e.g., the CERN telephone directory and guides to using CERN’s central computers); search functionality was based on keywords, because as we know, search engines debuted later.

Berners-Lee’s original Web browser running on the NeXT computers showed his vision and had many of the features of today’s Web browsers; it also included the ability to edit pages directly within the browser, the first Web editing feature.

Very rapid progress

Only a few users had access to the NeXT computer platform on which the first browser ran, but soon the development of a simpler, “line-mode” browser began; as early as 1991, Berners-Lee released his WWW software, which included precisely this “line-mode” browser, Web server software and a library for developers, and more generally the potential of the idea began to be understood and exploited.

Importantly, a HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) was created, which standardized communication between server and client, and it was at that stage that the software needed to use the World Wide Web system (basically the first text-based browser) was also made available outside CERN, with the activation of the first Web server in the United States, at Stanford University.

Several hands then began working on the project code, and in April 1993 CERN announced that “WWW technology would become freely usable by all, without having to pay any fees” to the same institute. By the end of that year there were more than 500 web servers, generating about 1 percent of Internet traffic.

More than thirty years of the WWW: what is the Web today

More than thirty years have now passed since that memorable date, as we were reminded by the Google doodle prepared to mark that momentous birthday, which shows an old desktop computer connecting to the Net, represented by a globe rotating on the monitor screen (a representation as faithful as it is nostalgic, for those who lived through the early days of connections).

The Internet and the Net are everyday life for billions of people, and it is virtually impossible to think of a world without these online services. But how has the Net changed in this time? To analyze people’s perceptions, in 2019 Cisco conducted special research on the topic by interviewing as many as 11 thousand subjects (one thousand Italians), as reported by Rai News: they all talk about the “huge impact the World Wide Web has had on our lives,” that the Net “continues to transform and change the world for the better.” In particular, the WWW has increased opportunities for entertainment, information and work, increased productivity and enabled new skills, but it also has the great merit of connecting people more and giving everyone a voice to express themselves.

The Web as a human right

There have also been more critical voices, however: for example, only one-third of Italians think that the benefits brought by the Internet outweigh the risks and only as many would not know how to do without it, but even the creators of the WWW themselves do not seem to be one hundred percent confident about what the use (current and future) of the system is. In his happy birthday message, Tim Berners-Lee says in particular that “we have a responsibility to make sure that the Web is recognized as a human right and built for the public good, because it has become a public square, a library, a doctor’s office, a store, a school, an office, a movie theater, a bank, and more.”

The meaning of the Web for Berners-Lee

Yet, according to the daddy of the WWW, “the gap between those who are online and those who are offline is growing. Today half the world is online: it is more urgent than ever to ensure that the other half is not left behind and that everyone contributes to a network that promotes equality, opportunity and creativity.” For Tim Berners-Lee, “the Web is for everyone, we have the power to change it,” starting with correcting some of the mistakes, sensitive issues and misuses such as “hacking, profit sacrificing user interests and the quality of online discourse sometimes characterized by hate speech.”

A message that is not too surprising to those familiar with Sir Berners-Lee’s thinking and philosophy: after leaving CERN, he moved briefly to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then, in 1994, started the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), an international community dedicated to the development of open web standards. The essential point for him was, and is, to ensure that the Web remains an open standard that can be used by everyone and that no one locks it into a proprietary system.

Specifically, the early Web community produced some revolutionary ideas that are still spreading far beyond the technology sector today:

- Decentralization: no permission from a central authority is needed to publish anything on the Web, there is no central control node, so no single point of failure…and no “kill switch”! This also implies freedom from indiscriminate censorship and surveillance.

- Non-discrimination: if I pay to connect to the Internet with a certain quality of service and you pay to connect with that or a better quality of service, then we can both communicate at the same level. This principle of fairness is also known as Net Neutrality.

- Bottom-up design: instead of being written and vetted by a small group of experts, the code was developed in the public eye, encouraging maximum participation and experimentation.

- Universality: for anyone to publish anything on the Web, all computers involved must speak the same languages to each other, regardless of the different hardware people use, where they live or what cultural and political beliefs they hold. In this way, the Web breaks down silos while allowing diversity to flourish.

- Consensus: for universal standards to work, everyone must agree to use them. Tim and others have achieved this consensus by giving everyone a voice in standards creation through a transparent and participatory process at W3C.

New permutations of these ideas are giving rise to new approaches in fields as diverse as information (Open Data), politics (Open Government), scientific research (Open Access), and education and culture (Free Culture), but so far we have only scratched the surface of how these principles could change society and politics for the better, as the World Wide Web Foundation, the foundation created in 2009 by Berners-Lee himself with Rosemary Leith, reminds us, advocating for a Web “that is secure, inspiring, and for everyone.”

Lights and shadows in these 30 years

Berners-Lee’s successor at the helm of Cern’s Web development team, François Flückiger, has also expressed his opinion on the Web’s first 30 years, saying he believes there are “positives and more negatives” and citing in particular as the most important change that the WWW has brought to society “the idea that anyone can be not only a consumer, but also a producer of information and, although not as often as I would like, of knowledge.”

Google’s unpredictable revolution

Among the most surprising points of this story, according to Flückiger, is one aspect of our business: “I had never imagined the search technology, so fast and efficient, that Google has invented,” says the computer scientist, who ranks the algorithm among the “three major breakthroughs of this new era, the other two being Ip and the Web,” admitting that “none of the engineers I know had even dreamed that something like this could happen,” just as unimaginable were ” the other Google applications, which are the result of the combination of their algorithms and their colossal computing power.”