Here comes E-E-A-T: Google adds Experience to its quality criteria

Goodbye E-A-T, the acronym we have been accustomed to using for years now in reference to the way Google and its quality raters evaluate whether pages provide useful and relevant information: on December 15, Google in fact released a new update to the official guidelines for its quality raters with which it introduces another letter-or rather another criterion, the E for Experience. From now on, therefore, we must learn to think E-E-A-T, an acronym that encompasses experience, expertise, authoritativeness and trustworthyness of the site and content authors.

Google’s Quality Rater Guidelines, the December 15, 2022 update

Just four and a half months after July 2022, Google has thus updated its guidelines for search quality raters for the second time this year, making some substantial changes to EAT, as we shall see.

As an ever-useful premise, let’s remember (as, moreover, Big G’s announcements also do) that the guidelines are the handbook used by quality raters as a compass to evaluate the performance of Google’s various Search ranking systems and do not directly affect ranking, but they are also useful for those who curate/manage a site to understand how to self-assess their content for success in Google Search.

Overall, the revised document is now about nine pages longer, reaching 176 pages compared to 167 pages in the previous version. As the final changelog appendix summarizes, the December 2022 version specifically introduces the following changes:

- Extensively updated concepts and classification criteria in “Part 1: Page Quality Guidelines” to make them more explicitly applicable to all types of Web sites and content creation models.

- Clarified directions on “Finding out who is responsible for the website and who created the page content” for different types of web pages.

- Added b with main “Page Quality Considerations” involved in PQ evaluation, leading to each PQ evaluation section (from lowest to highest).

- Refined/enhanced guidelines on the following key pillars of page quality assessment:

– “Quality of Main Content”

– “Reputation for Web sites and content creators”

– “Experience, expertise, authority and trust (EEAT)” - PQ assessment sections reordered from lowest to highest; simplified transitions

between these sections; deduplication of existing guidelines and examples as appropriate. - Added additional guidance and clarifications to the sections, “Pages with error messages

or without MCs,” “Forum and Q&A pages,” and “Frequently asked questions about page quality assessment.” - Reformatted lists of concepts and examples in tables (generally, where appropriate).

- General minor revisions (updated language, examples and explanations for

consistency between sections; obsolete examples removed; typos corrected; etc.).

The goal of this update is to make increasingly clear the importance of content, which, also following the path laid out with the Content Helpful System, should be created to be original and useful to people, as well as offering more detail to clarify and exemplify that useful information can come in a variety of different formats and from a range of sources.

As Lily Ray‘s excellent insight then notes, the document also seems to demonstrate Google’s focus on evolving its language to make it more inclusive and keep up with the times: for example, many new mentions of social media platforms, influencers, and how content can take different forms, such as videos, UGC, and social media posts, have been included. In addition, in the latest version Google also takes an even more granular approach in answering many common questions about how EEAT works and how much it matters for different topics, explains what content should be considered harmful, and whether daily experience is sufficient to produce reliable content for the topic in question.

Experience and Google’s new E-E-A-T criteria.

We said it before, though: the main change in this update concerns the addition of an extra E to EAT and quality dimensions for evaluating its search results. The new paradigm is thus officially called E-E-A-T or Double-E-A-T, with a more intense focus on the creator’s experience-which, by the way, was already part of Expertise in an implied way, so to speak, and thus is now only made official as an evaluative element in its own right.

The addition of “experience” indicates that the quality of content can be assessed by trying to understand whether and how much direct experience the content creator has on the topic.

The new acronym is thus E-E-A-T meaning experience, expertise, authoritativeness and trustworthiness, which in Italian we can translate as experience, expertise, authoritativeness and trustworthiness.

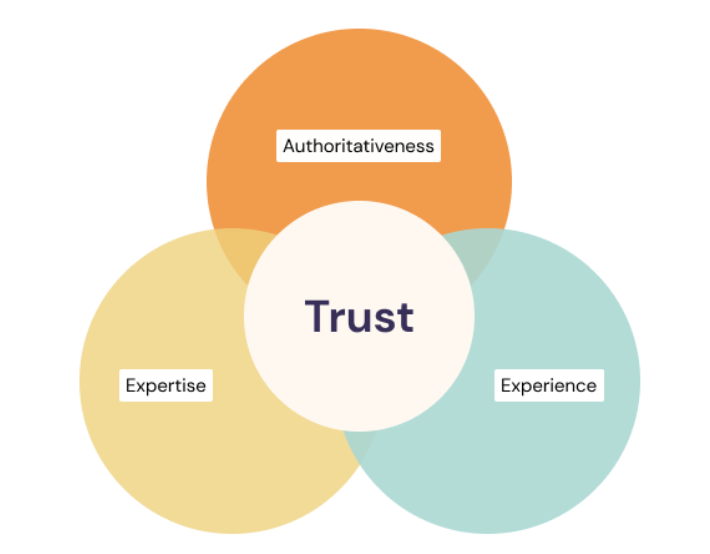

There is also another innovative aspect: now Google puts “trust” at the center of this concept, calling trustworthiness the “most important member of the EEAT family,” as seen in this diagram, and E-E-A are “important concepts that can support the evaluation of trust“.

According to Google, in fact, trust is “the extent to which the page is accurate, honest, safe, and trustworthy“, and untrustworthy pages “have a low EEAT, regardless of how much experience, expertise, or authority they can demonstrate.” From the perspective of quality raters, trust is the mechanism by which they are required to determine whether the page is “accurate, honest, safe, and trustworthy,” and the amount of trust a page requires depends entirely on the nature of the page.

What experience means to Google and how it is researched

The introduction of experience into the concept of EAT is consistent with many of Google’s updates and communications over the past two years on the characteristics required of content, particularly the aforementioned Helpful Content and the system on product reviews.

Just on the latter point, we can see how Google urges quality raters to look carefully at whether the content demonstrates that it was created “with some degree of experience, such as with the actual use of a product, after actually visiting a place or communicating what a person has experienced,” because there are some situations where what the user appreciates most and finds most useful is “content created by someone who has direct life experience on the topic in question.”

And so, says the information page on Mountain View’s blog, if the person is looking for “information on how to properly file a tax return” they will “probably want to see content produced by an expert in the field of accounting,” but if they are looking for “reviews of tax preparation software” they might be interested in a different kind of information, such as perhaps “a discussion forum with people who have experience with different services.”

In light of this new dimension, content creators must be able to demonstrate that they have the “first-hand experience needed for the topic”, because in some areas it is this significant experience that leads to trust. Thus, among the explanatory examples we find the case of a page with low EEAT if “the content creator does not have adequate experience, such as a restaurant review written by someone who has never eaten at the restaurant.”

These are not fundamentally new ideas, Elizabeth Tucker continues, and fit into the search engine’s broader philosophy, which “intends to surface reliable information, particularly on topics where quality of information is paramount.” The goal of these updates is to enable everyone-users as well as content creators-to better understand “the nuances of how people search for information and the diversity of quality information that exists in the world.”

The difference between Expertise and Experience

In defining quality, however, the context of information becomes central, because there are areas where experience and expertise jar and seem almost to be at odds.

Experience is that which comes from everyday life and real situations, while expertise is the training that determines the level of preparation of a content creator.

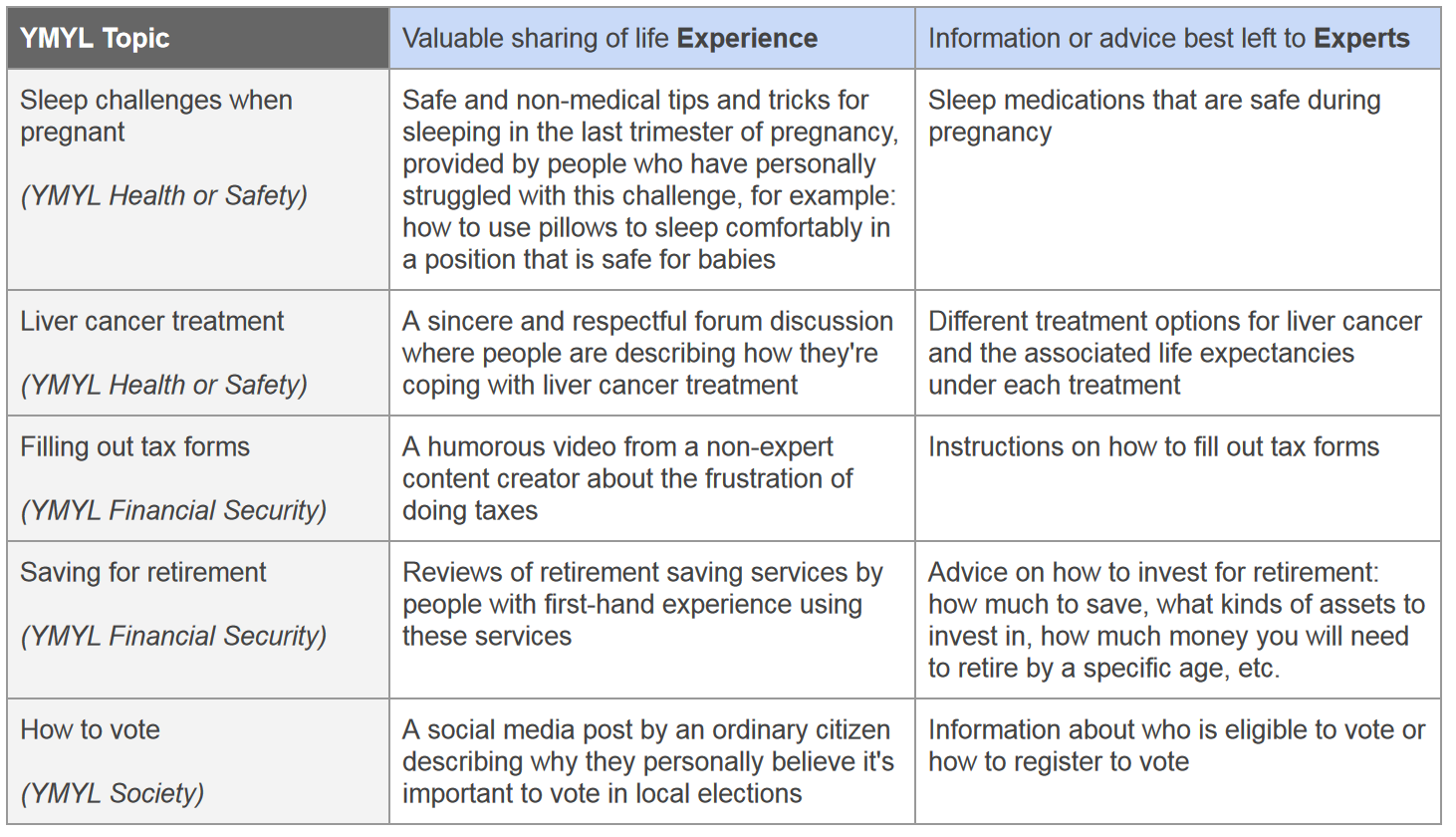

Google clarifies that “pages that share first-hand life experiences on clear YMYL topics can be considered with a high EEAT as long as the content is trustworthy, safe, and consistent with an established consensus of knowledgeable people“, but also that “some types of YMYL information and advice must come from knowledgeable experts”, as we also already knew.

The underlying meaning of this distinction is that people who share their stories based on their own direct experience can be considered reliable content in certain situations, but in others a more objective and qualified reference is always needed – reiterating that especially for YMYL topics, accuracy and alignment with expert consensus are important.

Google has therefore introduced a table within the document that helps distinguish when experience or expertise is needed for YMYL content, thus allowing us to better understand whether day-to-day experience or actual expertise is needed for various topics; furthermore, the fact that a content contributor is not a bona fide expert on a YMYL topic, this does not automatically make the content inherently unreliable, the guide says.

Search Quality Raters Guidelines, the other new features of the December 2022 update

Going back to the more general new features of the document updated on December 15, and Lily Ray’s painstaking work, there is now more direct guidance on understanding the people behind the website, and to be precise on identifying the person in charge of the site and the content creator, including analyzing the pages of the site itself to find out who these figures are and, therefore, who actually owns and operates the site.

In addition, it is emphasized that in evaluating the site, quality raters should not only focus on the domain in the abstract, but also refer to the reputation of the content creators and the people who contribute content to the pages.

From a practical standpoint, the person responsible for the Web site should be “clear,” and among the possible parties mentioned are “individual, company, business, organization, and government agency”; for some special cases, for example, “pages on Web sites such as forums and social media platforms, people may post content using an alias or username to avoid sharing personally identifiable information online.” In these situations, the guide says, “the alias or username is an acceptable way to identify the content creator.”

Instead, to more easily understand who created the main content of a web page, this table was introduced, which distinguishes cases on various types of sites and recognizes the possibility that some sites have full control of their content, while others consist primarily of user-generated content or author contributions. It is precisely in the latter case that it is important to be able to distinguish between the owner of the website and the actual contributors of the content on that site.

On the reputation side, then, the analysis “doubles up”: that of a site is based on the experience of real users and the opinion of people who are experts on the topics covered there, while that of content must be evaluated “in the context of the topic of the page” and must be identified for individual authors and content creators, among whom are mentioned (for the first time) influencers as well, reflecting an attempt to keep up with the evolving reality of the Net.

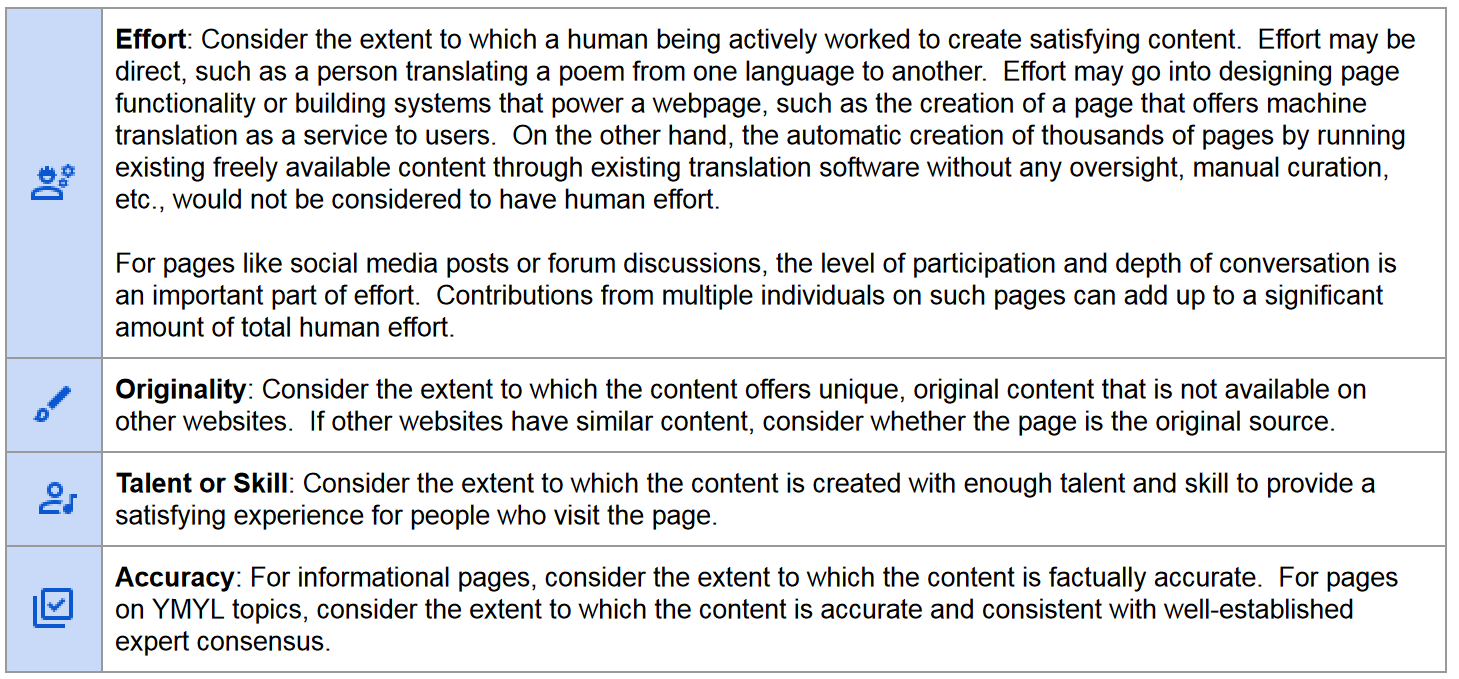

Finally, among the most notable additions is a new parameter to the elements that go into creating high-quality content, namely originality, which is added to “engagement, expertise and talent/skill” and replaces “time.” So now, per Google, “for most pages, MC quality can be determined by the amount of engagement, originality, and talent or skill that went into creating the content.”

Google thus seems to be asking raters to focus on how much actual work went into the creation of the content, as opposed to tactics that use automation without oversight or manual curation, with emphasis on content originality and the presence of insights not found elsewhere.

The value of guidelines for quality raters: why they are useful

All SEOs, content creators or otherwise professionals in search marketing should carve out some time to read Google’s new guidelines for quality raters: although, we reiterate, they do not directly affect rankings, they are a rather interesting and fairly accurate representation of the path Google has in mind for its algorithms.

Reading between the lines of this document can help us understand what Google is looking for in terms of content quality, user experience and EEAT of websites, thus making it easier to identify what features our pages should have even before we build and fill them with text.

Following these guidelines can serve us, in practical terms, to ensure that the site and brand can gain visibility in Google’s Search and, ideally, not be negatively affected by any of the algorithmic updates or other penalties.