Heatmap: cos’è e a cosa serve la mappa di calore

Si chiamano heatmap o mappe di calore e sono uno strumento potente e per capire cosa fanno gli utenti sulle pagine di un sito Web: dove fanno clic, fino a che punto scorrono, cosa guardano o ignorano. Rispetto agli altri tool di analisi, la mappa di calore è semplice e visiva: è un vero e proprio occhio digitale che ci permette di osservare e comprendere il comportamento degli utenti sul nostro sito web, fornendoci una panoramica più completa di come si comportano realmente le persone e delle zone in cui interagiscono meglio, così da avere un quadro dei punti di forza della pagina e, soprattutto, dei punti critici in cui possiamo intervenire con opportune correzioni. Proprio per questo le heat map sono un valido supporto anche alla strategia SEO e ci permettono di scoprire quali tipi di contenuti e immagini catturano meglio l’attenzione del pubblico e dove invece le persone incontrano difficoltà di navigazione.

Che cosa sono le heatmap o mappe di calore

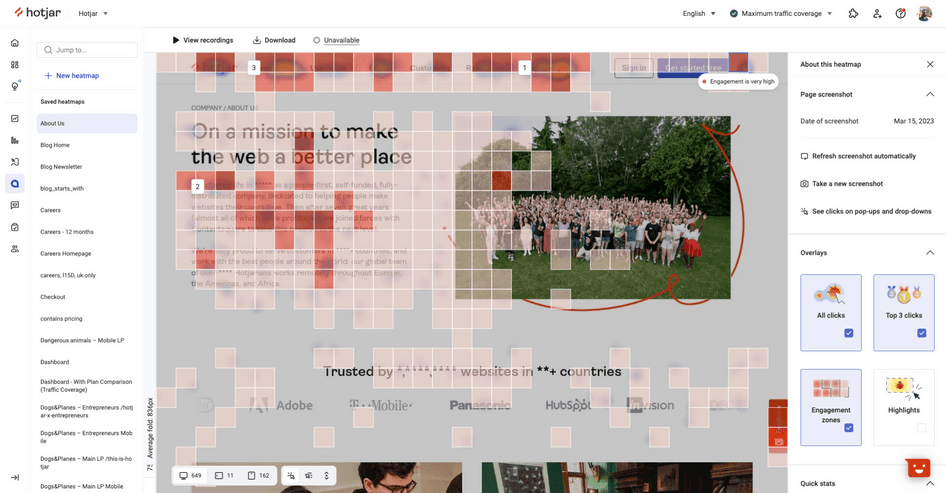

Le heatmap sono visualizzazioni di dati che utilizzano il colore per rappresentare i livelli di attività, coinvolgimento o attenzione degli utenti su una pagina web. Questi strumenti grafici ci consentono di vedere e analizzare in modo immediato come i visitatori interagiscono con il nostro sito.

A volte chiamate anche heat map (staccato) e mappa di calore o mappe termiche in italiano, le heatmap sono quindi una rappresentazione visiva dei dati di navigazione di una pagina web, che attraverso una scala cromatica mostrano immediatamente in che modo gli utenti interagiscono con quella pagina, in quali punti fanno clic e dove invece non cliccano, fino a che punto hanno fatto scorrere una pagina verso il basso o quali sono i risultati dei test di eye-tracking.

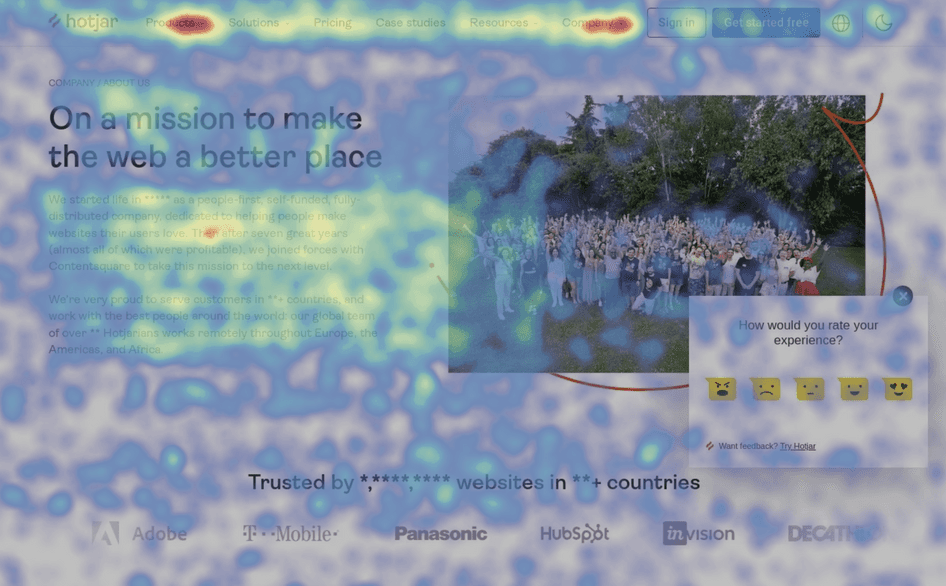

Più precisamente, la caratteristica chiave di una mappa di calore è fornire in forma grafica, attraverso una scala cromatica, le informazioni principali per visualizzare la quantità e la distribuzione di determinate variabili all’interno di un dataset. In questo senso, la heatmap è proprio una rappresentazione grafica di dati in cui i valori sono rappresentati da colori: di norma, il comportamento degli utenti è misurato su una scala dal rosso al blu, con il colore più caldo che indica il livello più alto di coinvolgimento e il più freddo che indica le aree con i livelli di coinvolgimento più bassi. Per semplificare, quindi, i colori più caldi, come il rosso e l’arancione, indicano aree di maggiore attività o interazione, mentre i colori più freddi, come il blu e il verde, indicano aree di minore attività.

Spiegazione della heat map

Nello specifico, le heatmap evidenziano le aree di maggiore interesse o interazione attraverso sfumature di colori: generalmente il rosso indica un’attività elevata, mentre il blu rappresenta un’attività bassa. Questo tipo di rappresentazione visiva rende molto più semplice l’individuazione dei pattern di comportamento, che potrebbero non essere evidenti attraverso i dati grezzi.

Le mappe di calore sono quindi uno strumento che consente di visualizzare graficamente le azioni che gli utenti compiono all’interno di pagine web, semplificando la visualizzazione di dati complessi e la loro comprensione a colpo d’occhio: l’idea di fondo è permettere a chi possiede o gestisce un sito di capire il rendimento di una pagina specifica e approcciare rapidamente alle informazioni di set di dati complessi grazie alla rappresentazione dei valori tramite il colore.

A cosa servono le heatmap

Le mappe di calore sono utilizzate in varie forme di analisi, ma sono più comunemente utilizzate per mostrare il comportamento degli utenti su pagine Web o template specifici di pagine Web, perché grazie alla codifica a colori consentono di comprendere subito quali parti di questa pagina ricevono maggiore attenzione, e quindi forniscono informazioni e spunti su come migliorare la struttura del sito o il posizionamento di determinati contenuti e risorse, come gli elementi cliccabili o il menu.

In effetti, le heatmap possono diventare essenziali per rilevare ciò che funziona o non funziona su un sito o su una specifica pagina di prodotto e per intervenire nell’ottimizzazione della web usability – la facilità di utilizzo e quindi di comprensione e navigazione del sito e delle sue pagine – che a sua volta può consentire di aumentare le conversioni. In termini pratici, sfruttando tecniche come gli A/B test per sperimentare il posizionamento di determinati pulsanti ed elementi sul sito, le mappe di calore consentono di valutare le prestazioni effettive della pagina e capire quali parti del nostro sito web attirano maggiormente l’attenzione degli utenti (dove cliccano, quanto scrollano, dove si soffermano di più), con l’obiettivo di utilizzare queste informazioni per aumentare il coinvolgimento e la fidelizzazione degli utenti , migliorando la loro esperienza di interazione col sito.

Ad esempio, se notiamo che gli utenti trascorrono molto tempo su una particolare sezione del nostro sito, potremmo decidere di posizionare lì i contenuti più importanti o le call to action. Oppure, al contrario, se notiamo che una determinata area del nostro sito viene ignorata, potremmo decidere di rivedere il layout o il design di quella sezione.

![]()

Quali sono i tipi di heatmap

Esistono diversi tipi di mappa di calore, ciascuna progettata per analizzare specifici elementi del comportamento dell’utente; essenzialmente, ogni tipo di mappa di calore fornisce quindi una prospettiva unica su uno specifico parametro dell’interazione dell’utente, visualizzandone graficamente le informazioni relative e offrendo insight preziosi che ci aiutano nella comprensione e nell’ottimizzazione del percorso utente sul nostro sito.ù

In base al tipo di analisi, lavorare con tali mappe ci consente di ricavare vari dati sul comportamento degli utenti e sul tipo di contenuto che attrae e trattiene il pubblico di destinazione, nonché di comprenderne meglio gli interessi e le esigenze del nostro target. Scegliere il tipo di heatmap più appropriato per le nostre esigenze è allora cruciale per ottenere dati significativi e azionabili.

Ecco quindi una panoramica delle principali tipologie di heatmap utilizzate nell’analisi del web.

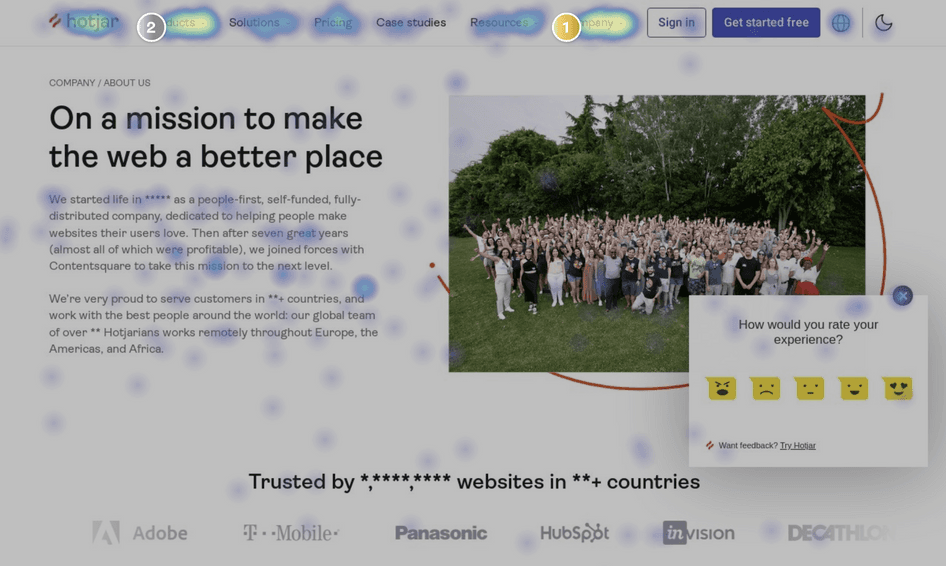

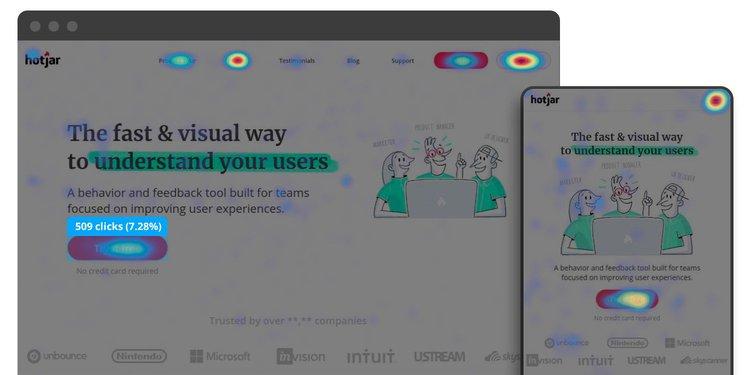

- Click Heatmap o mappe di calore dei clic mostrano esattamente dove gli utenti fanno clic su una pagina web. Sono appunto mappe che tracciano i clic e identificano cromaticamente le aree della pagina in cui utenti fanno clic più frequentemente o fanno tap da mobile. Analizzano tutte le azioni interattive dell’utente su elementi, come link interni, barra di navigazione, loghi, immagini, pulsanti CTA e tutto ciò che sembra essere cliccabile. Queste heatmap mostrano un aggregato dei punti in cui i visitatori fanno clic con il mouse sui dispositivi desktop o toccano con il dito sui dispositivi mobili (e si chiamano quindi anche mappe di calore touch), codificando con i colori caldi (rosso, arancione, giallo) gli elementi che sono stati cliccati e toccati di più e con i colori più freddi i punti che hanno un numero minore di clic. Queste mappe possono aiutarci a capire quali elementi del nostro sito attirano l’attenzione degli utenti e quali invece vengono ignorati. Per esempio, se una clic heatmap rivela che i visitatori stanno cliccando su elementi non cliccabili, potrebbe essere indicativo di un problema di usabilità o di design. Questo tipo di heatmap aiuta a ottimizzare il posizionamento delle CTA, dei link e di altri elementi interattivi, assicurandosi che siano facilmente accessibili e intuitivi per l’utente.

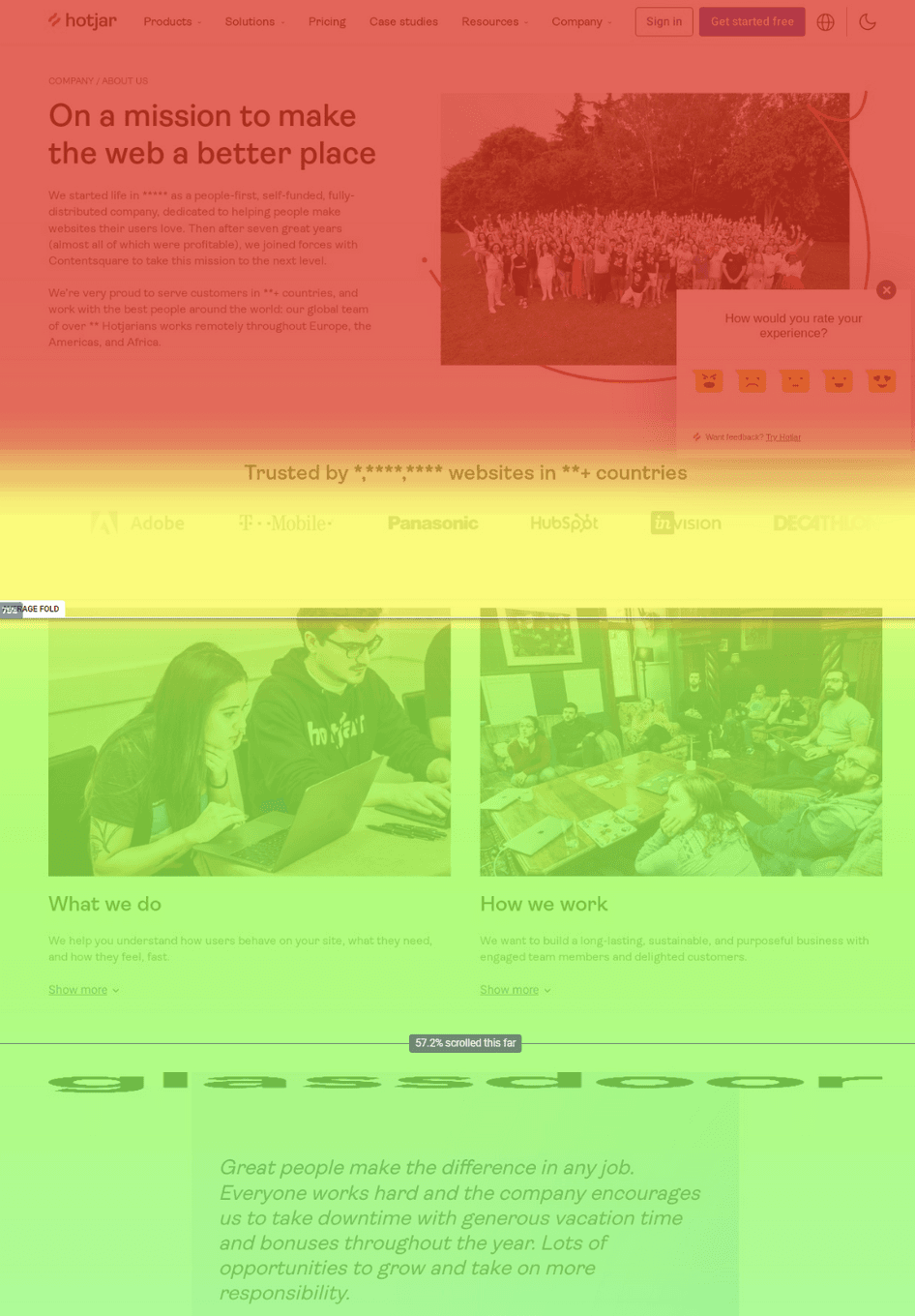

- Scroll Heatmap, o mappe di calore dello scroll, sono mappe che tracciano lo scorrimento e mostrano fino a che punto gli utenti scrollano una pagina web, monitorando quanto a fondo le persone scorrono in basso la pagina e mostrando le porzioni della pagina in cui i lettori arrivano prima di abbandonare la navigazione. Dal punto di vista visivo, più rossa è l’area, più persone la leggono, mentre se c’è prevalenza di azzurro e toni freddi vale la pena considerare di intervenire con opportune correzioni. Queste mappe sono utili per determinare se i visitatori stanno esaminando il contenuto complessivo della pagina o si fermano prima di raggiungere informazioni chiave. Queste indicazioni possono ad esempio aiutarci a capire se i nostri contenuti sono troppo lunghi o troppo corti e se gli utenti sono in grado di trovare facilmente le informazioni che cercano; inoltre, possono aiutarci a posizionare in modo ottimale i contenuti più importanti o le call to action. Se una scroll heatmap evidenzia che una parte significativa degli utenti non scorre fino a un’importante CTA o sezione di contenuto, è un segnale che potrebbe essere necessaria una riorganizzazione del layout della pagina, magari spostando le informazioni cruciali più in alto.

- Move Heatmap o mappe di calore del movimento, sono mappe di spostamento che tracciano il movimento del mouse degli utenti su una pagina web, mostrando le zone in cui le persone muovono il cursore all’interno della pagina. Possono servire a comprendere come le persone percepiscono i contenutie cosa li attrae di più, ma anche a scoprire elementi che li distraggono dal focus principale della pagina. Forniscono informazioni controverse e non pienamente affidabili: è vero che spesso gli utenti muovono il mouse in prossimità delle aree su cui stanno focalizzando la loro attenzione, ma ciò non vale in tutti i casi. Quindi, non possiamo sempre correlare direttamente i movimenti del mouse di un visitatore all’attenzione visiva o a ciò che sta effettivamente guardando: solo perché il mouse di un utente è rimasto sul titolo per 5 minuti, non significa che la persona stia ancora leggendo il titolo, e più in generale gli utenti non guardano sempre il punto esatto in cui si trova il loro mouse.

- Device Heatmap o mappe di calore per dispositivo, sono mappe di calore specifiche per i dispositivi desktop e mobile e servono a mostrare confrontarele interazioni degli utenti suddivise per tipo di dispositivo. Ad esempio, il contenuto che è prominente su una pagina desktop potrebbe trovarsi molto più in basso su un telefono, e quindi è cruciale vedere se l’interazione e l’esperienza utente siano diverse tra i vari device e lavorare per ottimizzare il nostro sito per tutti i tipi di utenti.

- Engagement Zone o mappe di calore per zone di coinvolgimento, sono strumenti che combinano set di dati di interazione derivanti da clic, scorrimento e spostamento delle mappe di calore in un’unica semplice visualizzazione. È un potente strumento di visualizzazione dei dati che suddivide una pagina web in sezioni o “zone”, mostrando il livello di interazione degli utenti con ciascuna zona in modo da aiutarci ad analizzare le pagine in pochi secondi attraverso una visione completa del coinvolgimento degli utenti con il nostro prodotto. In particolare, possono aiutarci a capire quali parti del nostro sito web sono più coinvolgenti per gli utenti e quali invece vengono ignorate. Ad esempio, le engagement zone potrebbero evidenziare la presenza in pagina di immagini che non ricevono clic, ma che sono gradite dagli utenti, che le osservano a lungo; oppure potremmo scoprire che gli utenti interagiscono molto con la nostra barra di navigazione, ma ignorano il footer. Queste informazioni possono guidarci nell’ottimizzazione del layout e del design del sito, permettendoci di concentrare i nostri sforzi sulle aree che hanno il maggiore impatto sull’esperienza utente.

- Rage Click maps o mappe di calore dei click di rabbia, sono un tipo di heatmap che visualizza le aree di un sito web su cui gli utenti cliccano ripetutamente in rapida successione, un comportamento spesso associato alla frustrazione o alla confusione. Queste mappe possono aiutarci a identificare le aree del nostro sito che causano problemi agli utenti e che necessitano di miglioramenti. Ad esempio, potremmo scoprire che gli utenti cliccano ripetutamente su un pulsante che non funziona correttamente, o su un link che non porta alla pagina prevista. Queste informazioni possono guidarci nell’identificazione e nella risoluzione dei problemi di usabilità, migliorando l’esperienza utente e riducendo la frustrazione degli utenti, in modo da aumentare le possibilità di aumentare le conversioni.

- Eye-Tracking Heat Maps o mappe di calore basate sul tracciamento oculare, sono mappe che mostrano dove gli utenti guardano su una pagina web o, per meglio dire, mostrano esattamente dove gli utenti rivolgono il loro sguardo mentre navigano su una pagina web. Queste mappe sono generate utilizzando tecnologie di tracciamento oculare, che rilevano e tracciano il movimento degli occhi degli utenti quando si trova sul sito e registrano i punti focalizzati dagli utenti, indicando anche la durata della visualizzazione; la loro creazione è affidata a laboratori che utilizzano solitamente webcam installate su dispositivi (o appositi strumenti che tracciano gli sguardi, messi a disposizione di utenti scelti come “tester”). Si tratta quindi di una visualizzazione avanzata che fornisce informazioni più dettagliate sul comportamento e sull’esperienza utente, e che quindi richiede attrezzature specializzate spesso risulta costosa da implementare. Questo tipo di analisi è estremamente preziosa perché ci permette di capire quali aree catturano maggiormente l’interesse visivo degli utenti. Le informazioni delle eye-tracking heatmap ci permettono ad esempio di scoprire se le immagini sono più attrattive dei testi o se ci sono sezioni della pagina che vengono completamente ignorate. Le eye-tracking heatmap forniscono insight dettagliati che vanno oltre il semplice clic o lo scroll, poiché ci dicono dove l’attenzione visiva si concentra e per quanto tempo: ad esempio, che le persone tendono a dare più rilevanza al lato sinistro del sito, è lì che sarà opportuno posizionare un logo, un banner e altre informazioni importanti. Attraverso queste informazioni possiamo quindi ottimizzare il layout, il design e il posizionamento dei contenuti al fine di massimizzare l’engagement e migliorare la user experience. Strumenti più avanzati come Tobii e Sensomotoric Instruments (SMI) sono spesso utilizzati in studi di usabilità per ottenere questi dati, rendendo le uno standard per chi desidera una comprensione più profonda del comportamento degli utenti sul web.

I vantaggi delle heatmap e delle informazioni che mostrano

Le heatmap sono uno strumento di visualizzazione dei dati estremamente potente, perché permettono di trasformare dati complessi in informazioni facilmente interpretabili: in pratica, ci permettono di “vedere” i dati, facilitando la scoperta di pattern e correlazioni che potrebbero essere difficili da identificare in altri formati.

Tuttavia, è importante ricordare che una mappa di calore non ci fornisce una spiegazione del perché gli utenti si comportano in un certo modo: mostra solo cosa gli utenti fanno sul nostro sito, non perché lo fanno. Per ottenere una comprensione più profonda del comportamento degli utenti, dovremmo combinare le informazioni fornite dalle heatmap con altri strumenti di analisi, come i sondaggi o le interviste agli utenti.

Al di là di questa e di altre criticità già segnalate, le heatmap (e in particolare quelle dei clic e di scorrimento) offrono comunque una rilevante serie di vantaggi, perché raccolgono passivamente dati su come gli utenti interagiscono con gli elementi della pagina di destinazione post-clic, di approfondire questioni relative all’esperienza dell’utente e al percorso del cliente sulla pagina di destinazione post-clic, di basare le valutazioni su dati reali di comportamento degli utenti senza dover più affidamento solo a ipotesi.

Come detto, tutto diventa poi visibile in pochi istanti, a colpo d’occhio e in modo chiaro per qualsiasi tipo di osservatore: di norma, il blu indica le aree con il livello più basso di attività degli utenti in base a vari indicatori, mentre il rosso segnala le “aree calde”, quelle in cui si concentra il più alto livello di interazione dell’utente.

Applicata alla pagina di un sito web, una heatmap mostra quindi come gli utenti reagiscono al contenuto e ai suoi diversi elementi, facendoci quindi comprendere a cosa è più interessato il pubblico, sia in termini di testo che di elementi cliccabili; grazie a questa visualizzazione, ad esempio, potremmo scoprire che i visitatori non stanno facendo clic sul pulsante CTA impostato, ma che cercano di fare clic su un elemento che non è selezionabile.

Approfondendo l’analisi, poi, possiamo valutare l’efficacia effettiva della pagina verificando con quante (e con quali) informazioni interagiscono i visitatori – ovvero, quanta parte della pagina leggono effettivamente, e quindi quali sezioni di contenuto sono interessanti e utili – e che tipo di azione intraprendono le persone (ad esempio, quali sono gli elementi su cui cliccano? Le aree di interesse strategico sono nella parte più visualizzata? C’è qualche elemento che viene ignorato?).

E quindi, le heatmap si caratterizzano nel fornire una guida visiva del comportamento dei visitatori e nel supportare gli analisti a vedere la pagina di destinazione attraverso gli occhi dei visitatori, così da trarre informazioni utili per apportare le modifiche necessarie all’ottimizzazione della pagina stessa per raggiungere gli obiettivi di incremento delle conversioni.

Con questo strumento, i professionisti del marketing possono monitorare il comportamento dell’utente, raccogliere dati da utilizzare per eseguire test A/B, ottimizzare la pagina e aumentare le conversioni e ottenere insights utili per prendere decisioni UX sulle pagine.

I dati delle heatmap aiutano a rispondere ad alcune domande relative al comportamento degli utenti e alla loro esperienza sulla pagina, che servono a raggiungere una comprensione più profonda sull’interazione dei visitatori e a far emergere eventuali aree critiche da cambiare nella pagina perché non funzionano. Tra le domande, ad esempio, ci sono:

- In che modo i visitatori stanno effettivamente utilizzando la pagina di destinazione post-clic?

- Come navigano sulla pagina di destinazione post-clic?

- Cosa attira la loro attenzione e dove tendono a fare clic?

- Quale elemento della pagina stanno ignorando?

- Fanno clic sul pulsante di CTA?

- Quanto è accattivante il copy?

- In quale area della pagina andrebbero posizionati gli elementi cruciali, che i visitatori non devono assolutamente ignorare?

Heatmap e SEO: come usare le mappe termiche per l’ottimizzazione

Praticamente qualsiasi sito web può beneficiare dell’uso delle heatmap: che si tratti di un blog, di un sito e-commerce, di un sito istituzionale o di un social network, le heatmap offrono insights preziosi sul comportamento degli utenti e permettono di orientare in modo più efficace le strategie e i messaggi.

Come detto, questi strumenti ci permettono essenzialmente di capire quali parti del nostro sito web attirano maggiormente l’attenzione degli utenti: ci mostrano dove gli utenti cliccano, quanto scrollano e dove si soffermano maggiormente, in modo da darci la possibilità di utilizzare queste informazioni per ottimizzare l’esperienza utente e per migliorare la chiarezza del sito e, anche, dei contenuti.

Le informazioni fornite dalle heatmap possono essere infatti utilizzate in vari modi: possono servire per testare diversi layout o design, per identificare eventuali problemi di usabilità, per capire quali contenuti sono più interessanti per i nostri utenti e molto altro ancora. Ad esempio, un sito e-commerce potrebbe utilizzare le heatmap per capire quali prodotti attirano maggiormente l’attenzione degli utenti, o per ottimizzare il processo di checkout. Un blog potrebbe utilizzare le heatmap per capire quali articoli sono più popolari, o per ottimizzare la posizione dei banner pubblicitari. Un sito istituzionale potrebbe utilizzare le heatmap per capire quali sezioni del sito sono più visitate, o per migliorare la navigazione del sito.

Quanto già scritto dovrebbe averci fatto comprendere perché le heatmap possono (e spesso sono) usate a supporto di una strategia SEO più ampia e onnicomprensiva: mai come negli ultimi anni appare sempre più chiaro che la SEO riguarda principalmente l’esperienza dell’utente prima ancora che il rispetto di regole per i robot. In effetti, oggi si parla di ottimizzazione dell’esperienza di ricerca più che di ottimizzazione per i motori di ricerca, perché è SEO curare ogni fase del search journey su Google, dalla prima impressione di un sito Web nei risultati di ricerca alla profondità, alla facilità e alla pertinenza delle informazioni che le persone trovano su un sito Web, perché solo capendo le richieste, gli interessi e le caratteristiche del pubblico di destinazione è possibile davvero ottimizzare il sito, ovvero renderlo attraente per le persone, che desiderano rimanere più a lungo sulle pagine e tornare per altre visite.

E quindi, per assicurare che la strategia sia efficace e ben impostata, monitorare il comportamento degli utenti del sito e valutare l’UX che ricevono quando utilizzano le risorse Web diventa fondamentale, e quindi le heatmap forniscono informazioni e dati efficaci per raggiungere questi obiettivi, insieme all’analisi di metriche come frequenza di rimbalzo, tempo sul sito, pagine visualizzate, frequenza di conversazione, che però non raccontano in profondità il vero rapporto della persona con la pagina.

Al contrario, una mappa termica ci consente di avere una finestra sulle pratiche comuni degli utenti su un sito e può aiutarci a determinare una serie di problemi che influiscono sulla strategia SEO, per capire quindi quali interventi correttivi attuare alla ricerca di soluzioni per migliorare l’esperienza utente complessiva e incrementare numero e qualità di visite e conversioni.

Quali aspetti delle pagine analizzare con le mappe termiche

Passando a consigli un po’ più pratici, sono diverse le informazioni utili alla SEO che ci arrivano dall’utilizzo delle heatmap.

Innanzitutto, con questo strumento e con l’analisi visiva possiamo approfondire meglio le effettive abitudini dei visitatori che interagiscono con le nostre pagine, scoprendo quali componenti ricevono maggiore attenzione, quali contenuti si rivelano più interessanti per il target, quali sezioni sono invece ignorate e fatte scorrere senza neppure uno sguardo, quali scelte di menu e filtri ottengono il maggior numero di clic.

Queste informazioni ci devono aiutare nel lavoro di rendere il sito il più semplice possibile da usare e nella ricerca di potenziali ostacoli che potrebbero ridurre l’engagement e i tassi di conversione, come sezioni, pulsanti o testi che possono distrarre l’utente o rendere negativa la sua esperienza.

Un altro aspetto concreto che si può migliorare grazie alle mappe termiche è il layout della pagina, che possiamo modellare su misura delle richieste, delle esigenze e dell’effettivo comportamento degli utenti, rimuovendo le zone di attrito e spostando gli elementi per noi più rilevanti nelle parti dove maggiormente si concentrano gli sguardi e gli interessi dei visitatori.

Scendendo ancora più in profondità, le heatmap ci sono aiutare a determinare il miglior stile del contenuto che presentiamo in pagina, ma anche la sua lunghezza ottimale: il word count resta un mito per la SEO, ma può aver senso scoprire se i lettori sono davvero interessati alla quota di testo che pubblichiamo e per capire il livello di informazioni di cui i visitatori hanno bisogno su una determinata questione. Se usiamo ad esempio una mappa a scorrimento possiamo identificare il punto in cui gli utenti lasciano più frequentemente la pagina Web e cercare di analizzarne i motivi: il contenuto precedente ha risolto il problema e fornito tutte le informazioni (e, quindi, la parte rimanente di testo è puramente “ornativa”)? O, al contrario, le persone non hanno trovato i dettagli a cui erano interessati e quindi magari tornano al motore di ricerca per lanciare altre query? Combinando questi insights con l’analisi del search intent relativo alla pagina di interesse, possiamo sperimentare la pubblicazione di testi di lunghezza diversa per determinare ciò che piace di più al pubblico e costruire una content strategy su misura delle esigenze del nostro pubblico.

Questo ultimo consiglio rientra a pieno nel primo utilizzo pratico delle heatmap, ovvero il supporto ai famosi Test A/B, che servono a valutare la percezione dell’utente e decidere se sia conveniente apportare modifiche alla pagina (e di che tipo): monitorando la reazione di diversi gruppi di utenti agli interventi correttivi proposti sarà possibile prendere la decisione giusta in modo più consapevole e ottimizzare la risorsa nel migliore dei modi.

Infine, con le heatmap possiamo avere uno strumento per migliorare la nostra strategia di link interni e, in parte, anche di linking esterna. Come sappiamo, i collegamenti interni sono essenziali per connettere le pagine del sito e impostare una gerarchia di contenuti sulle pagine più popolari: con le mappe termiche possiamo avere informazioni specifiche su dove gli utenti fanno clic e ottimizzare il posizionamento dei link, indirizzando più traffico alle pagine correlate.

Per quanto riguarda la linking esterna, invece, le heatmap ci aiutano in due modi: ci permettono di scoprire quali collegamenti ottengono il maggior numero di clic e di verificare se gli utenti prestano attenzione al tipo di autorevolezza del dominio linkato.

Ad esempio, alcuni lettori potrebbero seguire un collegamento rivolto a siti web/istituzioni, ma non cliccare su link verso siti meno noti; allo stesso modo, alcune persone potrebbero lasciare la pagina dopo aver incontrato un link in uscita che percepiscono come spam o irrilevante, e quindi cambiare la destinazione, rivolgendo il link a una fonte migliore, potrebbe essere un primo intervento immediato per invertire la rotta, prima di passare alle modifiche del contenuto stesso.

Heatmap per la SEO: le conclusioni

Provando a tessere le fila di questo discorso così lungo, di sicuro le heatmap ci aiutano ad avere indicazioni per migliorare la struttura e l’usabilità del sito, indicatori molto importanti per la user experience e “base” su cui poggiare i contenuti (ben ottimizzati per rispondere al search intent) con l’obiettivo di conquistare le migliori posizioni nei risultati di ricerca e aumentare il traffico organico.

È chiaro, però, che le mappe termiche sono solo uno strumento da usare insieme agli altri all’interno di una più ampia strategia SEO, e non un elemento che, da solo, può cambiare magicamente le sorti del progetto.

Inoltre, ci sono alcuni aspetti legati all’uso e alla comprensione delle heatmap su cui bisogna soffermarsi: innanzitutto, come per altri tipi di strumenti di web analytics, anche alle mappe di calore serve una grande quantità di dati – accurati e, soprattutto, generalizzabili – prima di poter essere affidabili. Analizzare le heatmap sulla base di campione molto ridotto è simile a chiudere un test A/B troppo presto, sulla base di pochissime visite o conversioni; poiché le mappe di calore mostrano le tendenze, è importante disporre di informazioni sufficienti per garantire che eventuali anomalie non influiscano sull’immagine complessiva dello strumento stesso.

È quindi importante essere consapevoli dei limiti delle mappe di calore che, se utilizzate in modo errato, possono essere fuorvianti e incoraggiare gli analisti a fare ipotesi che potrebbero non essere corrette: il primo punto è impostare il giusto approccio, ricordando che le heatmap ci dicono cosa è successo su una pagina, ma non possono dirci perché è successo.

Serve quindi anche una consapevolezza nella lettura dei dati e nell’interpretazione delle aree termiche: ad esempio, le mappe dei clic relative a una pagina con un modulo possono mostrare che gli utenti fanno molti clic sul primo campo e che ci sono meno clic sui campi successivi. A prima vista, ciò potrebbe suggerire che gli utenti stiano abbandonando il processo dopo aver compilato il primo campo, ma in realtà è più probabile che le persone proseguano la compilazione dei campi usando la tastiera anziché il mouse. Le heatmap non offrono questa informazione, che invece è disponibile negli appositi strumenti di analisi dei form, che misurano il tempo trascorso all’interno di ciascun campo, anziché solo i clic.

Come funzionano le mappe di calore

Esistono diversi strumenti per capire quale sia l’impatto dei nostri contenuti e della loro organizzazione sugli utenti, e ad esempio Google Analytics è un miniera di dati per comprendere come le persone arrivano sul nostro sito, quante e quali pagine visitino e da quale pagina abbandonano la navigazione, ma non ci permettono di entrare nel dettaglio dell’interazione effettiva.

Il concetto su cui si basa l’applicazione delle heatmap al web è invece il seguente: scroll, movimenti e click del mouse vengono analizzati e, attraverso specifici software, trasformati in concentrazioni di colore che permettono di vedere la densità di utilizzo delle varie sezioni di una pagina.

Le aree con cui l’utente interagisce maggiormente sono quelle marcate con colori caldi, come rosso e arancione, invece verde e blu (o comunque colori generalmente freddi) identificano le zone con meno interazioni: basta quindi davvero solo un colpo d’occhio per capire e vedere quali parti di una pagina ricevono maggiore attenzione e quindi trarre indicazioni su come migliorare la struttura o la visibilità della pagina.

Aggregando il comportamento degli utenti, le mappe di calore facilitano l’analisi dei dati, combinando dati quantitativi e qualitativi, e forniscono un’istantanea di come il target di destinazione interagisca con un singolo sito o pagina di prodotto, su cosa fa clic, scorre o ignora, sulla porzione media “fold” (la parte della pagina che le persone vedono sullo schermo senza scorrere non appena ci atterrano).

In questo modo, le heat map offrono a esperti di marketing, analisti digitali e di dati, UX designer, specialisti di social media e chiunque operi nel digital marketing informazioni approfondite sul comportamento delle persone sul proprio sito, aiutandoli a identificare tendenze, scoprire quali sono i limiti della pagina che bloccano le conversioni e, di conseguenza, quali sono le azioni possibili per aumentare il coinvolgimento e le vendite.

Mappe di calore per il sito web: gli strumenti principali

Scegliere e utilizzare gli strumenti giusti è essenziale per sviluppare mappe di calore accurate e rappresentative del comportamento degli utenti. Diversi software e piattaforme sul mercato rendono questo processo accessibile anche a chi non ha competenze tecniche avanzate e oggi il mercato offre diverse opzioni, ognuna con caratteristiche specifiche. Hotjar è uno dei software più popolari, noto per la sua interfaccia user-friendly e per le sue molteplici funzionalità, che oltre alle heatmap includono registrazioni delle sessioni e sondaggi agli utenti. Crazy Egg è un’altra scelta eccellente, con una gamma di strumenti visivi che permette di vedere non solo dove gli utenti fanno clic, ma anche quali parti ignorano; offre inoltre la funzione “Confetti”, che distingue i clic per referrer e segmenti di pubblico. Mouseflow va oltre le semplici heatmap (che comunque possono analizzare clic, movimento del mouse e scrolling), offrendo funzionalità come le session recording, che registrano interamente le sessioni degli utenti, e le funnel analysis, che identificano drop-off points nei percorsi di conversione. Similarmente, Lucky Orange offre un’ampia gamma di funzionalità per l’analisi del comportamento degli utenti, tra cui heatmap di clic, scroll e movimenti del mouse, e include anche session recording, chat in tempo reale e sondaggi per migliorare la user experience.

Come detto, non c’è invece una funzione di heat map in Google Analytics, nemmeno in GA4: è ancora disponibile un’estensione browser gratuita chiamata Page Analytics (di Google), che serviva a generare mappe di clic dai dati di Google Analytics, ma non è più supportata.

Heat map sito: come si implementano e come si sfruttano

Decidere di utilizzare una heatmap e scegliere il tool adatto è solo il primo passo: l’implementazione deve essere eseguita in modo accurato per garantire che i dati raccolti siano utili e significativi.

Ecco alcune tecniche chiave per la corretta implementazione delle heatmap.

- Definire gli obiettivi. Prima di tutto, è fondamentale avere una chiara comprensione di ciò che si desidera ottenere dalle heatmap. Che si tratti di aumentare le conversioni delle CTA, migliorare l’usabilità del sito o ottimizzare il layout delle pagine, gli obiettivi guideranno il processo di raccolta e analisi dei dati.

- Selezionare le pagine rilevanti. Non tutte le pagine del sito potrebbero richiedere un’analisi tramite heatmap. È utile concentrarsi su quelle pagine che sono critiche per il business, come le landing page, le pagine di prodotto e le pagine di checkout. Analizzare le pagine con alto traffico e quelle con tassi di conversione problematici può fornire insight preziosi.

- Inserire il tracking code. Una volta selezionato lo strumento, è necessario inserire il tracking code fornito dallo strumento scelto nel codice HTML del sito web. Di solito questo richiede di aggiungere un piccolo frammento di codice JavaScript nella sezione

<head>delle pagine che si desidera monitorare. Questo step è cruciale per garantire che i dati raccolti siano accurati. - Segmentazione e test. Per ottenere analisi più approfondite, è utile segmentare il traffico in base a variabili come dispositivo (desktop, mobile, tablet), nuova visita vs. ritorno, e origine del traffico (organico, paid, social). L’efficacia delle heatmap aumenta quando si conducono test A/B o multivariati. Testare diverse versioni di una pagina e analizzare i dati delle heatmap per ciascuna variante può rivelare quali cambiamenti portano i migliori risultati.

- Analisi e iterazione. La raccolta dei dati è solo l’inizio. Analizzare le heatmap richiede un occhio attento per identificare pattern ricorrenti e anomalie. Le heatmap ci mostrano dove gli utenti cliccano, fino a dove scorrono una pagina e dove dirigono maggiormente il loro sguardo, ma spetta a noi interpretare questi dati per apportare modifiche significative al sito. Questo processo deve essere iterativo: implementare cambiamenti basati sui dati e continuare a monitorare per ulteriori miglioramenti.

- Integrazione con altri dati analitici. Per un quadro completo, è utile integrare i dati delle heatmap con altre metriche analitiche. Combinare l’analisi quantitativa (come le sessioni, il bounce rate, il tempo sulla pagina) con i risultati qualitativi delle heatmap fornisce una comprensione più profonda del comportamento degli utenti.

Implementando queste tecniche e utilizzando gli strumenti appropriati, le heatmap diventano un potente alleato per qualsiasi strategia di ottimizzazione del sito web, aiutando a migliorare l’engagement degli utenti e a raggiungere i propri obiettivi di business in modo efficace e misurabile.

Mappe di calore sito: perché sono utili e importanti

Le heatmap sono pertanto strumenti insostituibili in vari ambiti del digital marketing e dell’ottimizzazione dei siti web e si rivelano particolarmente utili per chiunque si occupi di user experience (UX), conversion rate optimization (CRO), o SEO, poiché forniscono un quadro chiaro delle aree di una pagina web che attraggono maggiormente l’attenzione degli utenti.

La loro utilità principale risiede nella capacità di trasformare dati complessi in rappresentazioni visive semplici e intuitive. Con una heatmap, possiamo analizzare rapidamente dove gli utenti si concentrano o quali sezioni della pagina lasciano ignorate. Questo è fondamentale per migliorare l’usabilità del sito e l’esperienza utente, identificando le aree che necessitano di ottimizzazione. Per esempio, possiamo comprendere se importanti call-to-action (CTA) sono visibili e attrattive, o se elementi cruciali del contenuto sono stati relegati in zone con scarsa visibilità. Inoltre, le heatmap sono utili anche in ambito SEO. Analizzando come gli utenti interagiscono con i nostri contenuti, possiamo capire quali sezioni della pagina motivano un maggiore coinvolgimento, e possiamo quindi ottimizzare il contenuto per migliorare i tassi di conversione e ridurre la frequenza di rimbalzo (bounce rate).

La storia delle heatmap: non solo informatica

Concludiamo con un excursus sulle origini e sull’evoluzione delle heatmap, che hanno un percorso interessante che parte dall’analisi fisica dei dati fino alle sofisticate tecnologie digitali odierne.

Pur essendo uno strumento molto attuale, infatti, la pratica di utilizzo delle mappe termiche ha avuto origine nel 19° secolo: il concetto di rappresentare i dati utilizzando gradienti di colore era infatti già emerso in campi come la meteorologia e la cartografia e in particolare le mappe di isoipse, utilizzate per rappresentare la topografia del terreno, presentavano già similitudini con le heatmap moderne. In effetti, l’obiettivo era lo stesso: rendere comprensibili a colpo d’occhio dati complessi, utilizzando variazioni cromatiche.

Ma fu soprattutto l’ombreggiatura manuale in scala di grigi a partire da una matrice di dati che ebbe diffusione e applicazioni molto utili soprattutto in ambito medico.

Ad esempio, nella metà del XIX secolo il medico britannico John Snow utilizzò una mappa per visualizzare la diffusione di un’epidemia di colera a Londra. Snow colorò le aree della mappa in base al numero di casi di colera, creando una sorta di primitiva heatmap che gli permise di identificare la fonte dell’epidemia e di prendere le misure necessarie per contenerla. Qualche anno più anni, nel 1873, lo statistico francese Toussaint Loua realizzò il primo esempio di mappa termica, creando un sistema di matrice di ombreggiatura per visualizzare le statistiche sociali nei distretti di Parigi, rappresentando i valori più grandi con piccoli quadrati grigi o neri e i valori più piccoli con quadrati più chiari.

Successivamente, altri studiosi hanno mostrato i risultati di analisi dei cluster permutando le righe e le colonne di una matrice per posizionare valori simili l’uno vicino all’altro in base al clustering, mentre negli anni Settanta Robert Ling ebbe l’intuizione di unire gli alberi a grappolo alle righe e alle colonne della matrice di dati, usando caratteri della stampante sovraccaricati per rappresentare diverse sfumature di grigio, una larghezza di carattere per pixel.

Un contributo alla diffusione delle heat map arriva dalla psicologia e dalle scienze cognitive, dove le sperimentazioni iniziali si concentravano sulla tracciatura dei movimenti oculari. Uno degli studiosi pionieri fu il psicologo russo Alfred L. Yarbus, che negli anni ’50 condusse esperimenti rivoluzionari sul tracciamento oculare per studiare le aree d’interesse visivo umano. Utilizzando dispositivi analogici, Yarbus riuscì a registrare i punti focalizzati dagli occhi su vari stimoli visivi. I suoi studi presentarono i primi esempi di mappe di calore, mostrando graficamente le aree con maggiore densità di fissazioni oculari.

Tuttavia, l’uso delle heatmap come le conosciamo oggi ha inizio negli anni ’90, con l’avvento della bioinformatica: i ricercatori iniziarono a utilizzare le mappe termiche per visualizzare i risultati degli esperimenti di espressione genica, in cui venivano misurate le quantità di migliaia di geni in diverse condizioni sperimentali, trasformando dati complessi in un formato facilmente interpretabile per andare alla scoperta di pattern e correlazioni. Più o meno nello stesso periodo, poi, esperimenti di psicologia visiva si servivano delle heatmap per studiare il percorso visivo degli occhi su un oggetto o una superficie. Con l’avvento della tecnologia informatica e del web, queste tecniche sono state adattate e potenziate per analizzare il comportamento degli utenti online.

In questa fase ricordiamo due momenti importanti per questo strumento, con la nascita dei primi software in grado di tracciare i movimenti del mouse e i clic degli utenti, trasformando questi dati in rappresentazioni visive: nel 1994 Leland Wilkinson ha sviluppato SYSTAT, il primo programma per computer in grado di produrre mappe di calore dei cluster con grafica a colori ad alta risoluzione, e più o meno nello stesso periodo Cormac Kinney (un software designer) ha registrato il nome “heat map” per descrivere un display 2D raffigurante informazioni sui mercati finanziari, utile per dare agli operatori di borsa un tool visuale per agevolare la lettura dei dati finanziari in tempo reale.

Per la cronaca, nel 2003 la società che ha acquisito l’invenzione di Kinney ha involontariamente lasciato scadere il marchio.

Con l’avvento del web, le heatmap hanno trovato una nuova applicazione: l’analisi del comportamento degli utenti online. Nel 2005, la società di analisi web Crazy Egg introdusse il primo servizio di heatmap per siti web, che permetteva ai proprietari dei siti di visualizzare le aree del loro sito che attiravano maggiormente l’attenzione degli utenti, fornendo preziose informazioni per ottimizzare l’esperienza utente e migliorare l’efficacia del sito.

Oggi, le mappe termiche possono essere create a mano, utilizzando fogli di calcolo Excel, o più semplicemente attraverso strumenti di analisi come il citato Hotjar, probabilmente il tool più famoso per questo scopo (da cui abbiamo tratto la maggior parte delle immagini in pagina).

Immagine di copertina da www.zuko.io via Flickr