Chi sono, come lavorano e che peso hanno i quality rater di Google

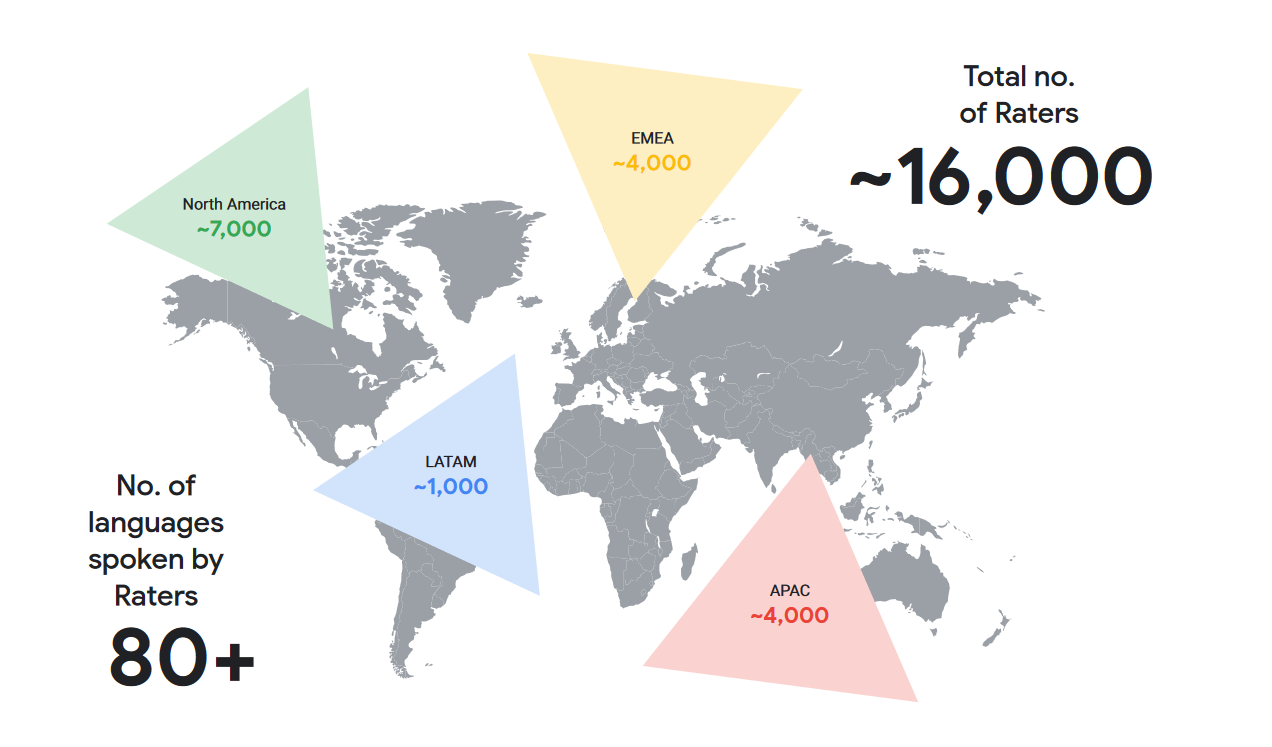

Una squadra di circa 16mila persone, attivi in tutto il mondo e impegnati in un compito specifico: valutare i risultati forniti da Google alla luce delle “Google Search Quality Rater Guidelines“, ovvero le linee guida pubblicate dalla compagnia, per scoprire se effettivamente le SERP rispettano i criteri segnalati e se, quindi, gli utenti ricevono un servizio efficace, utile e positivo. Oggi proviamo a scoprire qualcosa in più sui Google Quality Raters e sui documenti a cui devono far riferimento, per capire cosa fanno realmente, sfatare alcuni miti e, non meno importante, comprendere come il loro lavoro influisce sulla Ricerca e cosa bisogna sapere sul concetto di EEAT.

Chi sono i quality raters di Google

È almeno dal 2005 che Google ha lanciato il programma quality raters, coinvolgendo una folta schiera di tester, valutatori e revisori di qualità nel lavoro valutazione del suo prodotto finale, ovvero le SERP mostrate al pubblico, le pagine con i risultati di ricerca.

Dopo vari anni di indiscrezioni e speculazioni, nell’agosto 2022 l’azienda ha redatto un documento ufficiale (periodicamente aggiornato) che spiega chi sono e come lavorano queste figure, confermando di impiegare indirettamente circa 16mila quality rater in tutto il mondo, pagati a ora (13,5 dollari, pare), tramite un network di società appaltanti. Questi collaboratori esterni di Google sono assunti attraverso contratti di lavoro a termine e temporanei, che possono essere rinnovati ma che, in genere, non durano mai molto a lungo.

Queste persone sono il motore del “processo di valutazione della qualità della Ricerca” (Search Quality Rating Process), che misura appunto la qualità dei risultati della Ricerca su base continuativa grazie all’impegno dei 16mila Quality Raters esterni, che forniscono valutazioni basate su apposite linee guida e “rappresentano utenti reali e le loro probabili esigenze informative, utilizzando il proprio giudizio per rappresentare la propria località”, come chiarito da Google.

Come si diventa Google evaluator?

Intorno a questo programma c’è ovviamente una buona dose di riserbo e segretezza, e non esiste un modo per sottoporre la propria candidatura a quality rater né un ufficio o mail a cui inviare un curriculum: secondo quanto si può presupporre, è Google che contatta direttamente le persone che individua come potenziali valutatori ritenendole all’altezza del compito (a volte blogger sparsi in tutto il mondo), oppure delega in subappalto la ricerca ad agenzie specializzate.

La breve durata dei contratti ha una ratio ben specifica: impedisce ai quality raters di poter interferire in qualche modo con il sistema della ricerca andando oltre le proprie mansioni o di approfittare della propria posizione.

In questi 17 anni, il programma di Google ha impiegato milioni di QR, che sono stati gli occhi esterni e umani per vigilare sulla qualità delle SERP e dei risultati forniti.

Uscendo dal campo delle speculazioni, Google ha (finalmente) specificato chi sono effettivamente i Quality Raters, 16mila persone distribuite in varie parti del mondo (come si vede nella mappa, circa 4000 sono quelli impiegati per l’area EMEA, che comprende Europa, Medio Oriente e Africa) che rappresentano gli utenti di Search nella loro zona locale, così da assicurare la fondamentale diversità dei luoghi e l’efficienza nelle varie zone.

La compagnia americana ha ammesso che il recruiting è affidato a fornitori esterni e il numero effettivo dei QR può variare in base alle esigenze operative.

Le caratteristiche richieste per il lavoro sono “una grande familiarità con la lingua del compito e del luogo, per rappresentare l’esperienza delle persone locali” ma anche una comprensibile “familiarità e confidenza con l’uso di un motore di ricerca”.

Per quanto riguarda le altre richieste del datore di lavoro, poi, le valutazioni non devono basarsi su opinioni personali, preferenze, credenze religiose o opinioni politiche dei raters (come sancito anche dall’aggiornamento di dicembre 2019 delle linee guida per i quality raters di Google), che sono chiamati a “usare sempre il loro miglior giudizio e rappresentare gli standard culturali del loro Paese e luogo di valutazione”. Inoltre, per ottenere effettivamente l’incarico i potenziali raters devono superare un test sulle linee guida, che serve a garantire il rispetto degli standard di qualità di Google.

I compiti e le funzioni dei Quality Raters di Google

E quindi, cosa fanno questi Google evalutor? Possiamo pensare a loro come a un gruppo di revisori della qualità, che valutano i risultati di un’azienda sulla base di criteri, principi e documenti forniti dalla dirigenza.

Nel caso del motore di ricerca, i GQR sono incaricati di analizzare e studiare le informazioni contenute nei risultati delle query utilizzando le linee guida di Google e, soprattutto, le specifiche Search Quality Rater’s Guidelines, disponibili al pubblico online e costantemente aggiornate – la versione più recente è stata pubblicata nel novembre 2023.

I Google quality rater non determinano penalizzazioni, declassamenti o ban

È bene chiarire subito un aspetto: i collaboratori a progetto di Google non hanno accesso o controllo ad alcun componente degli algoritmi di Google e non determinano direttamente penalizzazioni, ban o cali di ranking per i siti.

La loro funzione non è decidere le posizioni dei risultati in SERP, ma solo verificare che il prodotto – vale a dire l’algoritmo di ricerca – stia funzionando nel modo previsto e secondo le regole prestabilite.

Ciò detto, con il loro giudizio i quality raters possono comunque influenzare indirettamente il posizionamento organico delle pagine, perché analizzano la qualità dei contenuti e assegnano una valutazione umana che sarà poi interpretata ed elaborata dai preposti team di Google.

Volendo sintetizzare, possiamo dire non influenzano il ranking dei siti che valutano, ma influenzano le classifiche di ogni sito rispetto alle query oggetto di valutazione. Per usare le parole di Google, i quality raters lavorano sulla base di un insieme comune di linee guida e ricevono compiti specifici da portare a termine. Le valutazioni aggregate servono a Google per misurare quanto i suoi sistemi stiano lavorando per fornire contenuti utili in tutto il mondo; in più, le valutazioni sono utilizzate per migliorare questi sistemi, fornendo loro esempi positivi e negativi di risultati di ricerca.

Un supporto anche per l’addrestamento del machine learning

Come nota l’esperta Marie Haynes, che ha lungamente studiato il tema, i Google rater sono un pezzo importante del puzzle del ranking attraverso cui possiamo scoprire qualcosa in più dei meccanismi interni dell’algoritmo di ricerca di Google, che ovviamente rimangono avvolti nel segreto.

Nello specifico, in aggiunta ai compiti “noti”, Haynes suggerisce che Google utilizzi le valutazioni dei suoi valutatori della qualità per fornire ai sistemi di apprendimento automatico esempi di risultati di ricerca utili e non utili, in particolare dopo il debutto di Helpful Content system.

In realtà, fino allo scorso anno Google aveva negato esplicitamente che i dati dei QR venissero utilizzati per addestrare i suoi algoritmi di classificazione del machine learning, ma ci sono segni che questa scelta sia cambiata negli ultimi anni.

Ad esempio, dal 2021 la pagina di Google su come funziona la Ricerca spiega che l’apprendimento automatico è usato nei loro sistemi di ranking:

Oltre alle parole chiave, i nostri sistemi analizzano anche se i contenuti sono pertinenti per una query in altri modi. Inoltre, utilizziamo dati aggregati e anonimi sulle interazioni per valutare quali risultati di ricerca sono pertinenti rispetto alle ricerche. Trasformiamo tali dati in indicatori che aiutano i nostri sistemi di machine learning a valutare meglio la pertinenza.

In maniera ancora più netta, poi, dal 2022 le linee guida dei QR chiariscono che le valutazioni sono utilizzate per misurare il rendimento degli algoritmi dei motori di ricerca e “anche per migliorare i motori di ricerca fornendo esempi di risultati utili e non utili per ricerche diverse” oppure “esempi positivi e negativi di risultati di ricerca“.

Tali etichette di risultati “utili” o “inutili” sono preziose per gli algoritmi di machine learning di Google: classificando i risultati della ricerca come “utili” o “non utili”, i valutatori della qualità forniscono un feedback umano reale da cui gli algoritmi possono imparare.

Come funziona il lavoro di valutazione umana sulla qualità dei risultati in SERP

Ogni quality rater ha il compito di verificare la qualità di un gruppo di SERP e quindi controlla una serie di pagine web (in genere, quelle meglio posizionate per le query più delicate); il suo compito è giudicare, in base a una precisa check-list, se il documento rispetta le linee guida relative alla qualità informativa e tecnica delle pagine.

Completata questa revisione, il quality rater assegna un rating di qualità, su una scala di voto da minimo a massimo: non è una valutazione soggettiva o personale, ma il margine di discrezionalità è molto limitato e il revisore deve rispettare in modo tassativo le citate linee guida redatte da Google. Questi dati sono poi forniti ai sistemi di machine learning, che li utilizzano per migliorare gli algoritmi basati sui fattori noti.

Grazie a questo lavoro, Google può individuare gli elementi di disinformazione che possono sfuggire ai sistemi algoritmici automatizzati. La mission dei quality raters è quindi quella di contribuire, attraverso un giudizio umano, a rendere le pagine dei risultati di ricerca utili e di alta qualità, riducendo la presenza di risultati fuorvianti e di contenuti non all’altezza degli standard.

Più precisamente, le valutazioni aggregate servono a misurare il livello di efficienza dei sistemi di Google nell’offrire contenuti utili in tutto il mondo, e sono inoltre usate per migliorare tali sistemi, fornendo esempi positivi e negativi di risultati di ricerca.

Rater Task: qual è il processo dietro alle valutazioni

Da questo punto di vista, è ancora il documento di Big G a chiarire come funziona il processo standard di valutazione (definito Rater Task): per prima cosa, Google genera un campione di ricerche (ad esempio, qualche centinaio) per analizzare un particolare tipo di ricerca o un potenziale cambiamento di classifica. A un gruppo di valutatori viene assegnato questo insieme di ricerche, su cui dovranno eseguire alcuni task: ad esempio, un tipo di compito è l’esperimento side-by-side, in cui ai Rater vengono mostrate due diverse serie di risultati di ricerca, una con la modifica proposta già implementata e una senza, per segnalare quali risultati preferiscono e perché.

Inoltre, i valutatori forniscono anche un prezioso feedback su altri sistemi, come l’ortografia. Per valutare i miglioramenti proposti al sistema ortografico, Google chiede ai valutatori se la query originale è scritta male e se la correzione generata dal sistema ortografico migliorato sia accurata per le singole query.

I raters esaminano anche ogni pagina elencata nel set di risultati e la valutano in base a scale di valutazione stabilite nelle apposite linee guida per i valutatori; la valutazione della qualità della ricerca si compone di due parti, come si vede in questa immagine.

Da un lato c’è il focus sulla “Page Quality“, la qualità della pagina – che cerca di determinare quanto la pagina raggiunge il suo scopo attraverso analisi del purpose stesso, valutazioni sugli eventuali rischi del contenuto e definizione della valutazione – e dall’altro invece l’attenzione sui “Needs Met” o soddisfazione dei bisogni dell’utente, che fa riferimento a quanto è utile un risultato per una determinata ricerca attraverso la determinazione del search intent (user intent) e della sua valutazione generale.

Anche qui, si ribadisce apertamente che “nessuna singola valutazione – o singolo valutatore – influisce direttamente sul posizionamento di una determinata pagina o sito nella Ricerca”. Anche perché, aggiunge il documento, “con trilioni di pagine che cambiano continuamente, non c’è modo che gli esseri umani possano valutare ogni pagina in modo ricorrente”, e pertanto utilizzare semplicemente le Search Quality Rating per il ranking non sarebbe fattibile, “poiché gli esseri umani non potrebbero mai valutare singolarmente ogni pagina sul web”.

Oltre a essere un compito impossibile, utilizzare solo i Search Quality Ratings per determinare il ranking non fornirebbe segnali sufficienti per stabilire come dovrebbe funzionare la classificazione stessa, e ci sono “così tante dimensioni della qualità e della rilevanza che sono fondamentali, come ad esempio i segnali che indicano qualcosa che potrebbe essere spam, segnalano che un sito potrebbe essere pericoloso o non sicuro o indicano che una pagina potrebbe essere obsoleta”.

Pertanto, chiosa il documento, “nessuna singola fonte di informazioni, come una valutazione della qualità della ricerca, potrà o potrebbe mai cogliere tutte le dimensioni importanti per un compito così complesso come il ranking”.

Il processo di valutazione: le indicazioni di Google sulla qualità delle pagine

Come accennato, la prima fase del lavoro dei quality rater si incentra sull’individuazione e sulla valutazione della Page Quality, vale a dire la qualità della pagina su cui sono chiamati a esprimersi.

L’obiettivo dei PQ rating process è di valutare quanto la pagina raggiunga effettivamente il suo scopo e si suddivide in tre step:

- Determinazione dello scopo o purpose

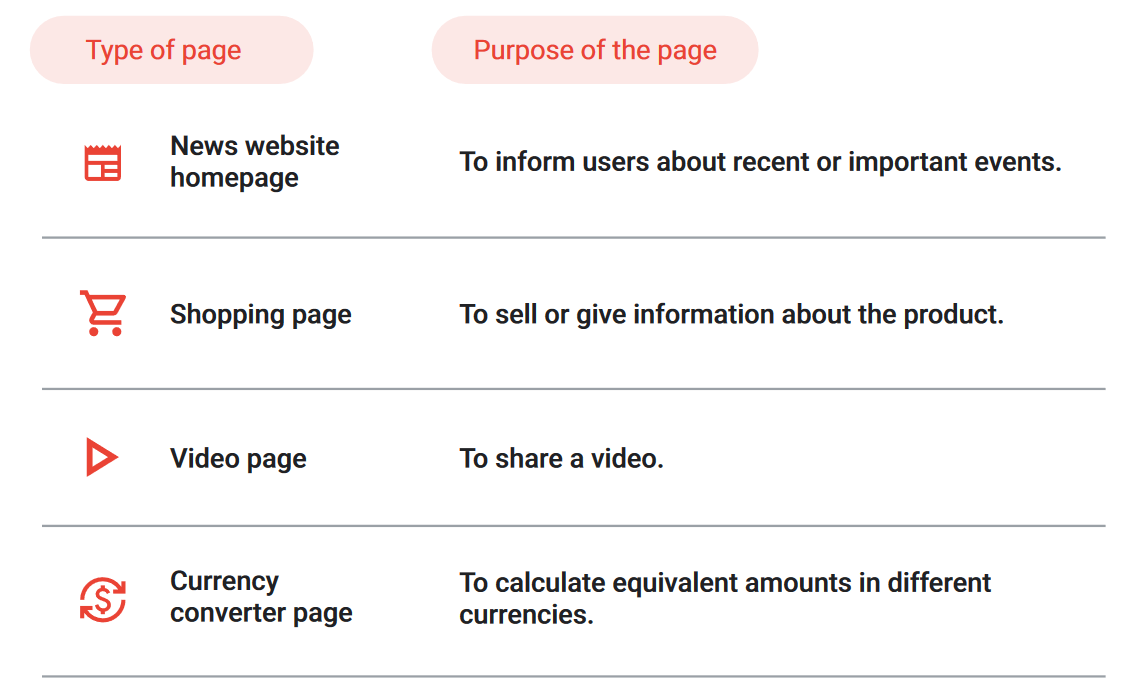

Per assegnare una valutazione, i valutatori devono innanzitutto comprendere lo scopo della pagina: ad esempio, lo scopo di una homepage di un sito di notizie è quello di informare gli utenti su eventi recenti o importanti, e così via per tutte le possibili tipologie di pagine e siti. Questo permette ai valutatori di capire meglio quali criteri sono importanti per valutare la qualità di quella pagina nella terza fase 3.

Google inoltre chiarisce che, essendoci tipi diversi di siti e pagine web che possono avere finalità molto diverse, le sue “aspettative e gli standard per i diversi tipi di pagine sono anch’essi diversi”.

Nel documento viene ribadito un altro aspetto molto interessante: per Google, i siti e le pagine web dovrebbero essere creati per aiutare le persone (e quando non ci riescono è giustificata e appropriata una valutazione di qualità Bassa). Quando le pagine sono utili e sono create per aiutare le persone, Google non fa distinzione di qualità tra un particolare scopo o tipo di pagina e un altro: detto in altri termini, le pagine di enciclopedia non sono necessariamente di qualità superiore rispetto alle pagine umoristiche, fin quando tutte aiutano l’utente.

Esistono pagine web di alta e bassa qualità di tutti i tipi e scopi diversi, come “pagine di shopping, pagine di notizie, pagine di forum, pagine di video, pagine con messaggi di errore, PDF, immagini, pagine di gossip, pagine umoristiche, homepage e tutti gli altri tipi di pagine”, e “il tipo di pagina non determina la valutazione PQ”, che invece viene determinata solo comprendendo lo scopo della pagina stessa.

- Valutazione sull’eventuale pericolosità dello scopo

Nel secondo step del processo, i quality raters sono chiamati ad accertare se lo scopo della pagina è dannoso o se la pagina può potenzialmente nuocere e provocare danni.

Se il sito o la pagina hanno uno scopo dannoso o sono progettati per ingannare le persone sul loro vero scopo, devono essere immediatamente classificati come di qualità più bassa relativamente al PQ. Sono di lowest quality, ad esempio, siti web o pagine che sono dannosi per le persone o la società, inaffidabili o di spam, come specificato nelle linee guida. Tuttavia, Google spiega che sul Web “ci sono molti contenuti che alcuni potrebbero trovare controversi, non imparziali, sgradevoli o di cattivo gusto, ma che non sono da considerarsi dannosi” ai sensi dei requisiti individuati da Google.

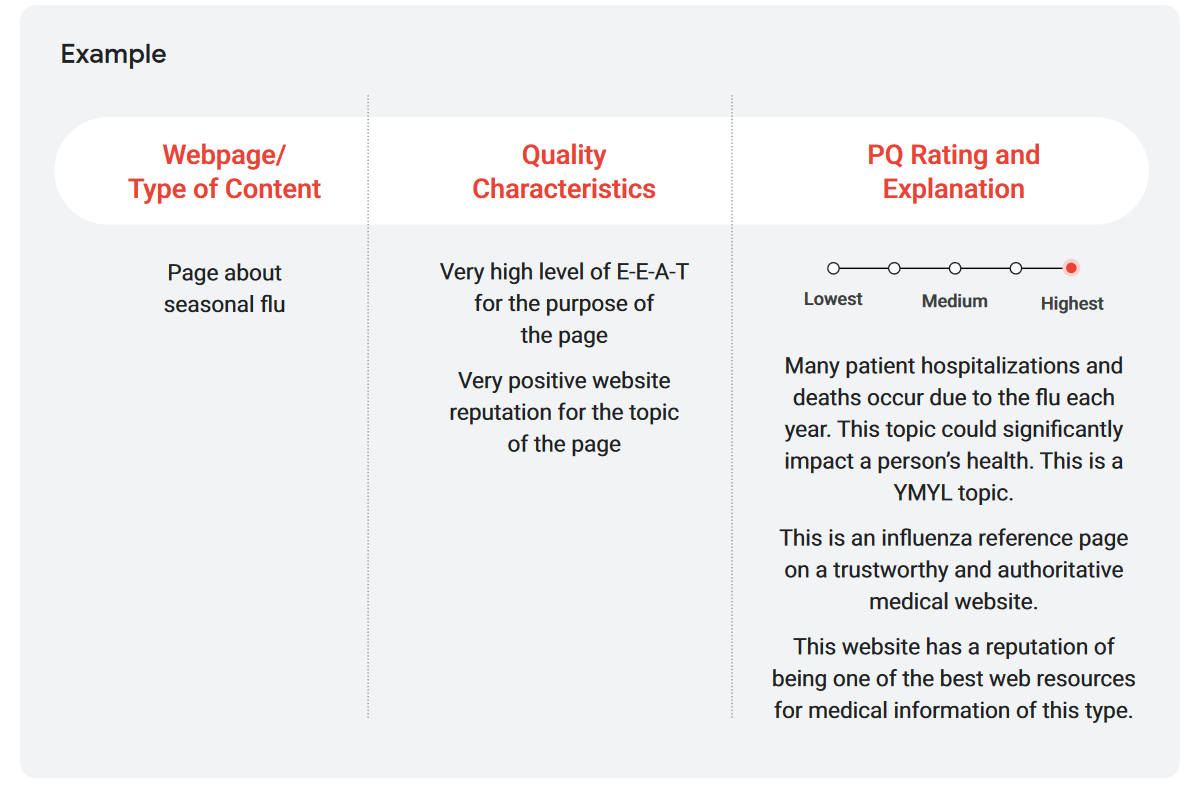

- Stabilire il rating

L’ultima fase è quella dell’effettiva determinazione della valutazione e, quindi, del PQ rating, che si basa sulla capacità della pagina di raggiungere il suo scopo su una scala che va da Lowest (minima) a Highest (qualità massima).

Il criterio principale per il voto di page quality è riferirsi ai parametri E-E-A-T della pagina, ovvero ai livelli di esperienza, competenza, autorevolezza e attendibilità che comunica. Nello specifico, i quality raters devono considerare e valutare:

- L’esperienza di prima mano del creatore del contenuto.

- La competenza del creatore.

- L’autorevolezza del creatore, del contenuto principale e del sito web.

- L’affidabilità del creatore, del contenuto principale e del sito web.

Nello specifico, il documento ufficiale spiega che i QR determinano il rating della Page Quality attraverso:

- Esame della quantità e della qualità del Contenuto principale (Main Content). Come regola generale, il contenuto principale è di alta qualità se richiede una quantità significativa di impegno, originalità e talento o abilità per essere creato.

- Esame delle informazioni disponibili sul sito web e sul suo creatore: deve essere chiaro chi è il responsabile del sito web e chi ha creato i contenuti della pagina, anche se usano pseudonimi, alias o username.

- Ricerca della reputazione del sito e del creatore. La reputazione di un sito web si basa sull’esperienza di utenti reali e sull’opinione di persone esperte dell’argomento trattato dal sito.

A proposito di topic, poi, qui Google fa riferimento esplicito alle pagine con contenuti YMYL o Your Money, Your Life, che richiedono standard di qualità diversi rispetto ad altri perché potrebbero “avere un impatto significativo sulla salute, sulla stabilità finanziaria o sulla sicurezza delle persone, o sul benessere della società”.

I raters sono chiamati ad applicare standard di PQ molto elevati per le pagine sugli argomenti YMYL, perché pagine di bassa qualità potrebbero avere un impatto negativo sulla salute, sulla stabilità finanziaria o sulla sicurezza delle persone, o sul benessere della società. Allo stesso modo dovrebbero ricevere la valutazione più bassa, altri siti web o pagine che sono dannosi per le persone o la società, inaffidabili o di spam.

Needs Met rating, il grado di soddisfazione dell’utente

Il secondo, grande, compito dei Google Quality Raters è la valutazione dei Needs Met o bisogni soddisfatti, in cui devono concentrarsi sulle esigenze degli utenti e sull’utilità del risultato per le persone che utilizzano Google Search – ed è proprio questo l’ambito su cui si è concentrato il lavoro di aggiornamento del 2023.

L’utilità di un risultato di ricerca riguarda l’intento dell’utente o search intent, come interpretato dalla query, e il grado di soddisfazione di tale intento (quanto il risultato soddisfi pienamente questo intento).

Ci sono quindi due fasi per la valutazione dei bisogni soddisfatti:

- Determinazione dell’user intent dalla query

Una query è “il testo, l’immagine e/o altro contenuto che un utente inserisce nella casella di ricerca di un motore di ricerca o di un’applicazione di ricerca per effettuare una ricerca” e possono “essere pronunciate, digitate, copiate e incollate, provenire direttamente da una fotocamera o un’altra applicazione e/o essere ricerche correlate che appaiono nei risultati di ricerca”, dice Google, che spiega di usare “contenuto della query e, se pertinente, la posizione dell’utente per determinare l’intento”.

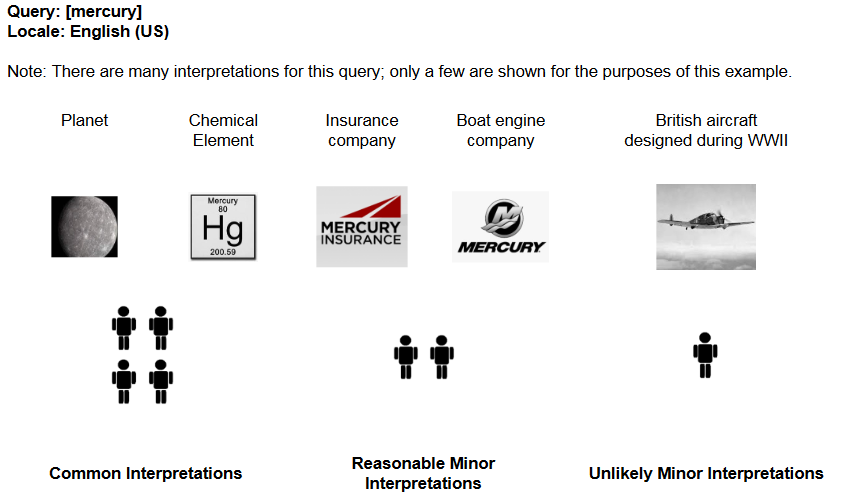

Ad esempio, se un utente cerca “caffetterie” e risiede a Londra, il motore di ricerca può determinare che il suo intento è trovare “caffetterie” nella capitale inglese. Tuttavia, molte query hanno anche più di un significato: ad esempio, il termine “mercurio” potrebbe legarsi all’intento di conoscere maggiori informazioni sul pianeta Mercurio o sull’elemento chimico.

Google parte dal presupposto che “gli utenti stiano cercando informazioni attuali su un argomento, e i valutatori sono istruiti a pensare al significato attuale della query mentre valutano” – e quindi effettivamente il fattore tempo e la freschezza hanno un valore e un peso.

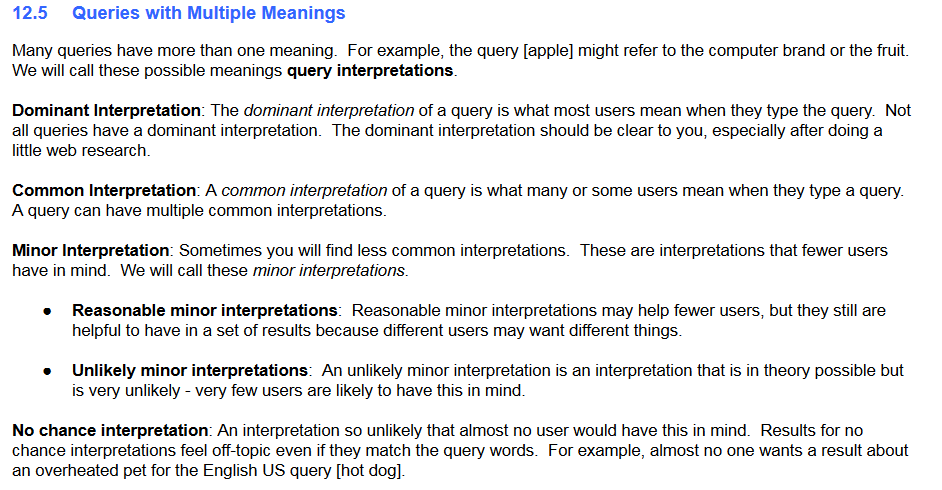

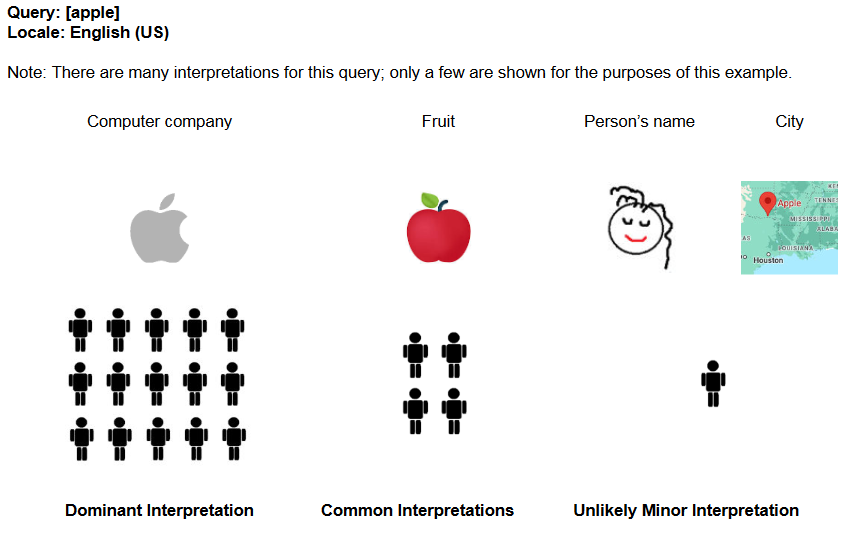

Altro aspetto aggiornato nel 2023 è la proprio definizione precisa di cosa Google intende per “interpretazioni della query“, ovvero il possibile significato – o più frequentemente i possibili e vari significati – di una query o di ciò a cui la query potrebbe riferirsi. Molte query possono infatti avere più di un significato, e ad esempio (in inglese, ma non solo) la query [apple] potrebbe riferirsi al marchio di computer o al frutto o a qualcos’altro.

Da questa valutazione deriva quindi l’individuazione di 4 categorie di probabilità di interpretazione:

- Interpretazione dominante. L’interpretazione dominante di una query è ciò che la maggior parte degli utenti intende quando digita la query. Non tutte le query hanno un’interpretazione dominante. L’interpretazione dominante dovrebbe essere chiara, specialmente dopo aver effettuato una breve ricerca sul web.

- Interpretazione comune. Un’interpretazione comune di una query è ciò che molti o alcuni utenti intendono quando digitano una query. Una query può avere molteplici interpretazioni comuni.

- Interpretazione minore. A volte si possono trovare interpretazioni meno comuni, quelle che meno utenti hanno in mente. Si suddivono in

- Interpretazioni minori ragionevoli. Le interpretazioni minori ragionevoli possono essere utili a meno utenti, ma sono comunque utili da avere in un insieme di risultati, perché diversi utenti possono desiderare cose diverse.

- Interpretazioni minori improbabili. Un’interpretazione minore improbabile è un’interpretazione che è teoricamente possibile ma molto improbabile – è molto raro che gli utenti la abbiano in mente.

- Interpretazione senza possibilità. Un’interpretazione così improbabile che quasi nessun utente la avrebbe in mente. I risultati per interpretazioni senza possibilità sembrano fuori tema anche se corrispondono alle parole della query. Ad esempio, quasi nessuno desidera un risultato riguardante un animale domestico surriscaldato per la query in inglese americano [hot dog]

Come spiega Lily Ray, le interpretazioni minori sono essenzialmente “i significati che hanno meno probabilità di essere quelli comunemente attesi della query”, e la distinzione successiva chiarisce che “Interpretazioni minori ragionevoli” sono quelle che aiutano “meno utenti” ma sono comunque utili per i risultati di ricerca, mentre le “Interpretazioni minori improbabili” sono teoricamente possibili ma altamente improbabili.

Google ha anche aggiunto alcuni nuovi esempi visivi su come interpretare queste definizioni: ad esempio, una “probabile interpretazione minore” della query di ricerca [Apple] sarebbe il nome di persona o la città degli Stati Uniti, Apple, Oklahoma; per [Mercury], invece, è ritenuto improbabile che molte persone siano interessate al velivolo aereo britannico progettato durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale.

- Determinazione del rating

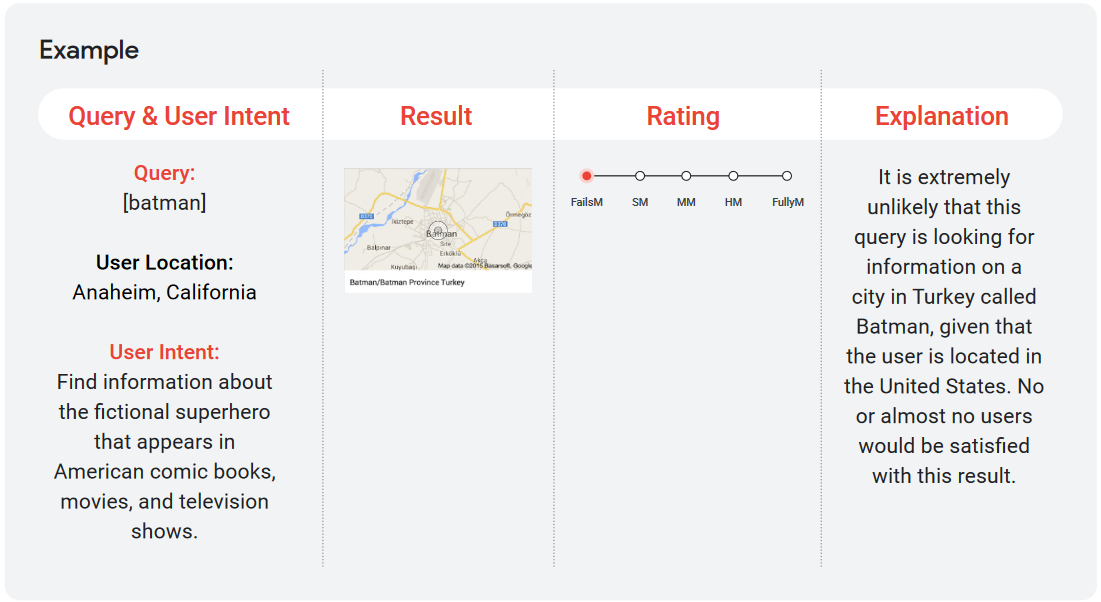

Il secondo step è la valutazione specifica del livello di Needs Met della pagina, che si basa su quanto un risultato di ricerca risponda all’intento dell’utente – altro focus cambiato nel 2023.

Per la valutazione valgono queste indicazioni:

- Fails to Meet (FailsM) / Soddisfazione fallita va assegnato a un risultato che fallisce completamente nell’intercettare i bisogni di tutti o quasi tutti gli utenti. Ad esempio, il risultato potrebbe essere off-topic per la query o potrebbe rispondere a un’interpretazione della query che è praticamente impossibile.

- Slightly Meets (SM) / Soddisfazione parziale va assegnato a un risultato che può essere di scarso aiuto per un’interpretazione prevalente, comune o ragionevolmente secondaria dell’intento dell’utente, oppure a un risultato che può essere utile ma per un’interpretazione dell’intento dell’utente o della query che è piuttosto rara o improbabile.

- Moderately Meets (MM) / Soddisfazione moderata va assegnato a un risultato che si rivela utile per qualsiasi interpretazione principale, comune o ragionevolmente secondaria dell’intento dell’utente o della query.

- Highly Meets (HM) / Soddisfazione elevata va assegnato a un risultato molto utile per qualsiasi interpretazione principale, comune o ragionevolmente secondaria dell’intento dell’utente o della query.

- Fully Meets (FullyM) / Soddisfazione Completa è una categoria di valutazione speciale, che si applica solo alle query con un intento chiaro di trovare un risultato specifico e il corrispondente risultato specifico che l’utente sta cercando. Si tratta, nella maggioranza di casi, di query di tipo navigational o con richiesta molto specifica (trovare un indirizzo, conoscere un’informazione certa e così via), che non presentano ambiguità di interpretazione.

Nel determinare la valutazione, il Quality Rater deve considerare la misura in cui il risultato:

- “si adatta” alla richiesta (calza a pennello la query, per così dire);

- è aggiornato;

- è preciso e affidabile per le richieste di informazioni;

- soddisfa l’utente.

Stando a questi criteri, un risultato valutato come “fully meets” (soddisfazione piena) significa che un utente sarebbe immediatamente e pienamente soddisfatto dal risultato e non avrebbe bisogno di visualizzare altri risultati per soddisfare le proprie esigenze. Al contrario, lo screen qui sotto mostra un caso di fallimento della soddisfazione, perché è “estremamente improbabile che [la persona che ha lanciato] questa query stia cercando informazioni su una città in Turchia chiamata Batman, dato che l’utente si trova negli Stati Uniti. Nessun utente o quasi nessun utente sarebbe soddisfatto di questo risultato”.

Le linee guida di Google per i quality rater

Il cuore di questa importante attività è quindi rappresentato dalle istruzioni contenute nelle linee guida per i Search Quality Rater, un documento che conta più di 150 pagine all’ultima versione e che scandaglia tutto ciò che significa qualità per Google, offrendo le indicazioni ai QR (ma in realtà a chiunque, essendo accessibile e pubblico) per portare avanti il proprio lavoro. Nello specifico, valutare i risultati di query campione e valutare in che misura le pagine elencate sembrano dimostrare caratteristiche di affidabilità e utilità.

Come si legge in apertura del documento, “le linee guida generali riguardano principalmente la valutazione della qualità della pagina (PQ) e la soddisfazione dei fabbisogni (NM, needs met in originale)”: in pratica, i quality raters hanno il compito di esprimere un giudizio e un voto sul modo in cui il motore di ricerca risponde a search intent (le esigenze) e livelli qualitativi richiesti.

L’interpretazione dell’utilità dei risultati

In un approfondimento su SearchEngineJournal, Dave Davies ci fornisce alcune indicazioni utili sul lavoro dei quality raters e in particolare sul processo di valutazione, che probabilmente si basa sulla domanda “Quanto è utile e soddisfacente questo risultato?”.

Durante il test, un valutatore può visitare una singola pagina web oppure concentrarsi su una SERP intera, analizzando ogni risultato posizionato. In entrambi i casi, invierà a Google dei segnali in merito alla struttura del sito, al dispositivo, alle differenze demografiche e ai risultati della posizione, più una serie di altri fattori che si applicano alla classificazione di ciascun risultato.

Questi dati serviranno a guidare le modifiche per migliorare i risultati e determinare algoritmicamente quali fattori o combinazioni di fattori sono comuni ai risultati con ranking più alto. La valutazione dei needs met richiede una qualità della pagina almeno decente e si basa sia sulla query che sul risultato.

Il lavoro umano è utile anche nell’interpretazione di query ambigue, come quelle che hanno molteplici risultati: in questi casi, il punteggio di NM deve dare più peso alle pagine che soddisfano intenti più elevati e ricercati, così da impedire il posizionamento alto di pagine che trattano topic che non corrispondono al search intent generale e l’invio di segnali sbagliati agli algoritmi, che quindi possono concentrarsi sui segnali giusti per la maggior parte degli utenti.

Le valutazioni sulla qualità delle pagine

In realtà, e come era facile intuire, le indicazioni per valutare la qualità delle pagine fornite ai tester umani non si discostano molto dalle best practices a cui classicamente si fa riferimento per i siti: le valutazioni si basano su una serie di fattori, tutti collegati tra loro, e il peso attribuito a ogni fattore si basa sul tipo di sito e query.

Ci sono alcune tipologie di topic e categorie che sono sotto una lente di ingrandimento speciale, e in particolare quello più attenzionato è il settore Your Money or Your Life (YMYL) per le possibili implicazioni nocive e dannose per una singola persona, per gruppi di persone o addirittura per l’intera società, e per questi argomenti i raters devono prestare maggiore cura e sono invitati a dare più peso all’EEAT.

La divisione dei contenuti del sito

Secondo le linee guida, le sezioni di un sito Web possono essere classificate in tre categorie principali:

- Contenuto principale (o main content, MC): qualsiasi parte della pagina che aiuta direttamente la pagina a raggiungere il suo scopo.

- Contenuto supplementare (o supplemental content, SC): contenuti aggiuntivi che contribuiscono alla buona esperienza dell’utente sulla pagina, ma non aiutano direttamente la pagina a raggiungere il suo scopo. L’esempio fornito dal documento sono i link di navigazione: un elemento essenziale per il sito, ma non necessario per soddisfare le esigenze dei visitatori.

- Annunci (Ads): advertising o monetizzazione sono contenuti e/o link che sono visualizzati in pagina allo scopo di monetizzare, ovvero ricevere soldi. La presenza o l’assenza di annunci non è di per sé un motivo per una valutazione di qualità alta o bassa: senza pubblicità e monetizzazione, alcune pagine web non potrebbero esistere, perché mantenere un sito web e creare contenuti di alta qualità richiede costi anche molti elevati.

La facilità di accesso e il volume del main content fanno la loro parte nei calcoli sulla qualità della pagina: è ciò che aiuta il rater a valutare non solo se sono soddisfatte le esigenze/intenti, ma anche se e quanto è facile accedere al contenuto supplementare, se lo si desidera.

Il focus su E-E-A-T

La sezione relativa al paradigma EEAT (in precedenza noto come E-A-T, con la E di esperienza in meno) è una delle più complesse e discusse, e spesso anche i Googler sono intervenuti per fornire chiarimenti e indicazioni su questi parametri (come ad esempio Gary Illyes nell’articolo linkato).

Il primo punto da comprendere è che Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness, le sigle di EEAT (in italiano Esperienza, Competenza, Autorevolezza, Affidabilità) non sono fattori di ranking su Google.

Sono i parametri che i quality rater cercano e utilizzano per orientarsi nella valutazione dei siti Web e per capire se i sistemi di Google funzionano bene nel fornire buone informazioni, ma non fanno parte di alcun algoritmo.

Il funzionamento è quindi il seguente: i rater usano i principi EEAT per giudicare i siti Web e Google utilizza le loro valutazioni per regolare il suo algoritmo. Quindi, alla fine l’algoritmo si allineerà ai principi EEAT, che possono esserci utili come principio guida nella progettazione del sito, nella creazione di contenuti e nel supporto ai segnali esterni.

Non c’è una ottimizzazione specifica che possiamo fare per questi parametri, ma possiamo comunque lavorare per migliorare il modo (complesso) in cui Google vede, interpreta e valuta il nostro sito e le nostre pagine e, quindi, per migliorare l’EEAT dei nostri contenuti, ad esempio lavorando su alcuni segnali che possiamo fornire al motore di ricerca.

Il peso di EEAT dipende comunque dal tipo di topic trattato, e le linee guida chiariscono che, a seconda dell’argomento, si deve assicurare l’esperienza di prima mano (meno formale, per così dire) o la competenza strutturata: rientrano nel primo caso, ad esempio, le recensioni estremamente dettagliate e utili di prodotti o ristoranti, la condivisione di consigli ed esperienze di vita su forum, blog eccetera e tutti i contenuti scritti da persone comuni che però hanno vissuro direttamente la situazione e possono essere quindi considerate esperte in tali argomenti senza che la persona/pagina/sito web abbiano un punteggio inferiore per il fatto di non avere un’istruzione o una formazione “formale” nel settore.

Google chiarisce anche che è possibile avere una competenza comune sugli argomenti YMYL: per esempio, ci sono forum e pagine di supporto per persone con malattie specifiche e la condivisione di esperienze personali è una forma di competenza comune; allo stesso tempo, però, informazioni e consigli medici specifici (e non quindi semplici descrizioni di esperienze di vita) dovrebbero provenire da medici o altri professionisti della salute, di comprovata professionalità.

In definitiva, possiamo dire che lo standard di competenza dipende dall’argomento della pagina, e per comprenderlo dovremmo chiederci quale tipo di competenza è necessaria perché la pagina raggiunga bene il suo scopo.

Google: i quality raters migliorano la Ricerca senza influire sul ranking

Questo tema resta controverso e ha generato nel tempo polemiche e veri e propri attacchi frontali (come quello del Wall Street Journal nel novembre 2019), al punto che anche Danny Sullivan, voce pubblica di Google, ha firmato un articolo in cui spiega come vengono implementate le modifiche al ranking della Ricerca, soffermandosi in modo particolare sul ruolo dei quality raters di Google in questo processo.

Un sistema di ricerca in continua evoluzione per migliorare sempre

“Ogni ricerca che fai su Google è una di miliardi che riceviamo quel giorno”, esordisce il Public Liaison for Search di Mountain View, che ricorda come “in meno di mezzo secondo, i nostri sistemi selezionano centinaia di miliardi di pagine Web per cercare di trovare i risultati più pertinenti e utili a disposizione”.

Ma questo sistema non può essere statico, lo sappiamo, anche perché “le esigenze del Web e delle informazioni delle persone continuano a cambiare”, e quindi Google apporta “molti miglioramenti ai nostri algoritmi di ricerca per tenere il passo”, al ritmo di migliaia all’anno (come i 3200 cambiamenti nel solo 2018 o i 5150 del 2021, ad esempio), con l’obiettivo di “lavorare sempre a nuovi modi per rendere i nostri risultati più utili, sia che si tratti di una nuova funzionalità, sia che offrano nuove modalità di comprensione della lingua alla ricerca” (è il caso esplicito di Google BERT).

Questi miglioramenti sono approvati al termine di un preciso e rigoroso processo di valutazione, progettato in modo che le persone in tutto il mondo “continuino a trovare Google utile per tutto ciò che stanno cercando”. E Sullivan sottolinea che ci sono alcuni “modi in cui insights e feedback delle persone di tutto il mondo aiutano a migliorare la ricerca”.

Il compito del team di ricerca di Google

In linea generale, Google lavora per rendere più facile per le persone trovare informazioni utili, ma la vastità della platea determina anche che gli utenti abbiano esigenze di informazione diverse a seconda dei loro interessi, della lingua che parlano e della loro posizione nel mondo.

Quindi, la mission di base è rendere le informazioni universalmente accessibili e utili, e a questo contribuisce lo specifico team di ricerca di Google (research team) che ha il compito di entrare in contatto con persone di tutto il mondo per capire come la Ricerca (con la maiuscola, nel senso di Search) può essere più utile. Le persone sono invitate a fornire feedback su diverse iterazioni dei progetti, o è lo stesso gruppo di lavoro a fare ricerche sul campo per capire come gli utenti nelle diverse comunità accedono alle informazioni online.

L’esempio di Google Go: insights per rispondere alle esigenze

Sullivan racconta anche un esempio concreto: “nel corso degli anni abbiamo appreso le esigenze uniche e le limitazioni tecniche che hanno le persone nei mercati emergenti quando accedono alle informazioni online”, e questo ha portato allo sviluppo di Google Go, “un’app di ricerca leggera che funziona bene con telefoni meno potenti e connessioni meno affidabili”. Sulla stessa app, successivamente, Google ha introdotto “funzionalità straordinariamente utili, tra cui una che consente di ascoltare le pagine web ad alta voce, particolarmente utile per le persone che imparano una nuova lingua o che potrebbero essere a disagio con la lettura di testi lunghi”, che non sarebbero state sviluppate senza i giusti insights delle persone che alla fine le usano.

L’impegno per la qualità dei risultati

Di pari passo c’è il lavoro costante sull’effettivo funzionamento del motore di ricerca e sulla qualità dei risultati proposti agli utenti. Come dice il Googler, “una parte fondamentale del nostro processo di valutazione è ottenere feedback dagli utenti di tutti i giorni sul fatto che i nostri sistemi di classificazione e i miglioramenti proposti stiano funzionando bene”.

Ovvero, che le SERP facciano emergere contenuti di qualità, come spiegato in modo dettagliato nelle linee guida per il search quality rating (lunghe attualmente più di 160 pagine), il cui senso si può sintetizzare dicendo che “la Ricerca è progettata per restituire risultati pertinenti dalle fonti più affidabili disponibili”.

Per determinare alcuni paramenti, i sistemi di Google utilizzano automaticamente “segnali dal Web stesso – ad esempio, dove compaiono sulle pagine Web le parole della tua ricerca o come le pagine si collegano tra loro sul Web – per capire quali informazioni sono correlate alla tua query e se sono informazioni di cui le persone tendono a fidarsi”. Tuttavia, le nozioni di pertinenza e affidabilità “sono in definitiva giudizi umani, quindi, per misurare se i nostri sistemi li stanno effettivamente capendo correttamente, dobbiamo raccogliere insights e indicazioni dalle persone”.

Chi sono i Search quality raters

È questo il compito dei search quality raters, un “gruppo di oltre 10.000 persone in tutto il mondo” che aiuta Google a “misurare il modo in cui è probabile che le persone entrino in contatto con i nostri risultati”. Questi collaboratori e osservatori esterni “forniscono valutazioni basate sulle nostre linee guida e rappresentano gli utenti reali e le loro probabili esigenze di informazione, usando il loro miglior giudizio per rappresentare la loro località”. Queste persone, specifica Sullivan, “studiano e sono testate sulle nostre linee guida prima di poter iniziare a fornire valutazioni”.

Come funziona una valutazione

L’articolo sul blog The Keyword descrive anche il processo standard della valutazione dei quality raters, in versione ridotta e semplificata rispetto a quello su riportato (ma è interessante leggerlo anche per “scoprire le differenze”).

Google genera “un campione di query (diciamo, poche centinaia), che assegna a un gruppo di rater, a cui sono mostrate due versioni diverse delle pagine dei risultati per tali ricerche [una sorta di test A/B, in pratica]. Un set di risultati proviene dall’attuale versione di Google e l’altro set deriva da un miglioramento che stiamo prendendo in considerazione”.

I raters “riesaminano ogni pagina elencata nel set di risultati e valutano quella pagina rispetto alla query”, facendo riferimento alle indicazioni contenute nelle citate linee guida, e in particolare “stabiliscono se quelle pagine soddisfano le esigenze di informazione in base alla loro comprensione di ciò che quella query stava cercando” (ovvero, se rispondono al search intent) e “prendono in considerazione elementi come quanto autorevole e affidabile quella fonte sembra essere sull’argomento nella query”.

Le analisi sul paradigma EEAT

Per valutare i “parametri come competenza, autorevolezza e affidabilità, ai raters viene chiesto di fare ricerca reputazionale sulle fonti”, e Sullivan offre un ulteriore esempio per semplificare questo lavoro.

“Immagina che la query sia ricetta della torta di carote: il set di risultati può includere articoli da siti di ricette, riviste alimentari, marchi alimentari e forse blog. Per determinare se una pagina web soddisfa le esigenze di informazione, un valutatore può considerare quanto siano facili da comprendere le istruzioni di cottura, quanto sia utile la ricetta in termini di istruzioni visive e immagini, e se ci siano altre utili funzionalità sul sito, come uno strumento per creare una lista della spesa o un calcolatore automatico per modificare le dosi”.

Allo stesso tempo, “per capire se l’autore ha esperienza in materia, un rater farà qualche ricerca online per vedere se l’autore ha qualifiche nel cooking, se ha profili o referenze su altri siti Web a tema food o ha prodotto altri contenuti di qualità che hanno ottenuto recensioni o valutazioni positive su siti di ricette”.

L’obiettivo di fondo di questa operazione di ricerca è “rispondere a domande del tipo: questa pagina è degna di fiducia e proviene da un sito o un autore con una buona reputazione?”.

Le valutazioni non sono usate per il ranking

Dopo che i valutatori hanno svolto questa ricerca, forniscono quindi un punteggio di qualità per ogni pagina. A questo punto, Sullivan sottolinea con forza che “questa valutazione non influisce direttamente sul posizionamento di questa pagina o sito nella ricerca”, ribadendo quindi che il lavoro dei quality rater non ha peso sul ranking.

Inoltre, “nessuno sta decidendo che una determinata fonte è autorevole o affidabile” e “alle pagine non vengono assegnati rating come un modo per determinare quanto bene classificarle”. E non potrebbe essere altrimenti, dice Sullivan, perché per noi questo “sarebbe un compito impossibile e soprattutto un segnale mediocre da usare: con centinaia di miliardi di pagine che cambiano costantemente, non c’è modo in cui gli umani possano valutare ogni pagina su base ricorrente”.

Al contrario, il ranking è composto da “un data point che, preso in forma aggregata, ci aiuta a misurare l’efficacia dei nostri sistemi per fornire contenuti di qualità in linea con il modo in cui le persone, in tutto il mondo, valutano le informazioni”.

A cosa servono le valutazioni

Ma quindi a cosa servono in concreto questi interventi umani? Lo spiega ancora Sullivan rivelando che solo lo scorso anno Google ha “effettuato oltre 383.605 Search quality test e 62.937 esperimenti fianco a fianco con i nostri search quality raters per misurare la qualità dei nostri risultati e aiutarci a fare oltre 3.600 miglioramenti ai nostri algoritmi di ricerca”.

Gli esperimenti dal vivo

A questi due tipi di feedback si aggiunge un ulteriore sistema usato per apportare miglioramenti: Google deve “capire come funzionerà una nuova feature quando è effettivamente disponibile in Ricerca e le persone la usano come farebbero nella vita reale”. Per essere sicuri di poter ottenere queste informazioni, la compagnia testa “il modo in cui le persone interagiscono con le nuove funzionalità attraverso esperimenti dal vivo”.

Questi test live sono “effettivamente disponibili per una piccola parte di persone selezionate casualmente utilizzando la versione corrente di Ricerca” e “per testare una modifica, avvieremo una funzione su una piccola percentuale di tutte le query che riceviamo ed esaminiamo una serie di metriche diverse per misurare l’impatto”.

Si tratta di avere risposte a domande come “Le persone hanno fatto clic o tap sulla nuova funzione? La maggior parte delle persone lo ha ignorato? Ha rallentato il caricamento della pagina?”, che generano insights che “possono aiutarci a capire un po’ se quella nuova funzionalità o modifica è utile e se le persone la useranno effettivamente”.

Sempre lo scorso anno, Google ha “eseguito oltre 17.000 esperimenti di traffico in tempo reale per testare nuove funzionalità e miglioramenti alla ricerca”. Confrontare questo numero con quello effettivo delle modifiche apportate (circa 3600, come detto prima), si comprende come “solo i potenziamenti migliori e più utili approdano in Google Search”.

L’obiettivo di offrire risultati sempre più utili

Ammettendo che “i nostri risultati di ricerca non saranno mai perfetti”, Sullivan conclude dicendo che però “questi processi di ricerca e valutazione si sono dimostrati molto efficaci negli ultimi due decenni”, consentendo a Google di “apportare frequenti miglioramenti e garantire che i cambiamenti apportati rappresentino le esigenze delle persone di tutto il mondo che vengono alla ricerca di informazioni”.