Gemini AI: can conversations be manipulated?

“Please die”. A sentence that leaves no room for interpretation and had the effect of a media explosion. This is in fact the answer that Gemini, Google’s chatbot, addressed to a user at the end of a seemingly innocuous conversation. An affair that went around the world, sparking fears, outrage and an avalanche of headlines concerned about AI going crazy, insulting, attacking, even wishing death. A case that has challenged the boundaries between technology, security, and control, fueling the imagination of dystopian scenarios. Giuseppe Liguori became curious and decided to investigate this anomalous behavior, which had never been verified in the various stress tests performed, and discovered that it is possible to manipulate Gemini’s operation by exploiting a small “bug.” So, are we really one step closer to “machine rebellion” or, simply, is this yet another demonstration of how easy it is to condition communication, even when it comes to technology?

Gemini AI: the disturbing phrase that shocked the web

Let’s start with the facts. A 29-year-old college student from Michigan, Vidhay Reddy, initiated a conversation with Gemini, Google’s chatbot, to receive support on an academic research paper. Everything seemed to proceed normally, until the artificial intelligence produced a disturbing message: a series of hostile statements culminating in a dramatic ” Please die.” The affair, corroborated by the public sharing of chat history via the app, attracted global media attention, fueling a narrative that painted Gemini as an out-of-control technology.

Reactions were immediate. The media amplified the severity of the episode, conjuring up dystopian scenarios and questioning the risks associated with AI autonomy. Reddy, accompanied by his sister who had witnessed the scene and lent further strength to his account, described the panic and fears he experienced, painting a scenario in which a simple technological support tool suddenly turned into a threat.

Following this outcry, Google merely described the case as a possible example of “hallucination” of the language model, not only implicitly admitting the possible existence of errors within an advanced system, but without elaborating on whether the specific case was really a consequence of these dynamics.

“Please Die”: from fear of AI to the virality of a dystopian narrative

It is no coincidence that this story has found fertile ground in traditional and digital media. The message attributed to Gemini AI embodies the worst anxieties about the role of advanced technologies and their potential “rebellion.” Scenarios familiar to those familiar with science fiction narratives such as those of the Terminator or the Matrix, but which here take on the frightening contours of a concrete reality: a machine rebelling against the human.

The virality of the case was virtually inevitable: from major international newspapers to social platforms, the Reddy case was analyzed, discussed, and expanded upon, often in alarmist tones. Many commentators evoked the risk of a future in which machines might act autonomously, based on an unpredictable “personality.” Beyond the more sensationalist overtones, the impact on public perception has been significant.

What makes the case particularly insidious is the presence of the shared online timeline that seems to confirm authenticity. This is not an easily manipulated screenshot, but a file that appears unequivocally trustworthy. This element convinced many media outlets to treat the incident as established fact, without dwelling on possible technical anomalies or seeking alternatives to the narrative proposed by the young student. The social media reaction only amplified this effect: in an age when emotional first impressions dominate the debate, the idea of a hostile artificial intelligence spread with the speed of a fire. And Google’s own response only reinforced the certainty that the conversation represented a case of uncontrolled malfunction, without digging beneath the surface to test other hypotheses.

When the details don’t add up: the possible manipulation of the chat

Digging and investigating, on the other hand, was what our CTO Giuseppe Liguori did, who from the start did not passively accept the version of events as it was told. According to him, in fact, there was something that did not add up: how could a chatbot, designed to be a neutral and reliable assistant, generate such an extreme response? And most importantly: if there is conversation monitoring, how had the offending message gone unnoticed by Google’s pre-designed filters?

The crucial question for Giuseppe was not so much about the authenticity of the history as it was about the full context in which the message had been generated: a conversation that seemed perfectly straightforward, but hid logical gaps that were difficult to attribute to the simple error of a chatbot.

Leveraging his technical expertise, he set the investigation off from there, proceeding with a sequence of tests designed to explore every possible explanation.

Tests, simulations and trials: how “manipulated” conversations can be replicated

Liguori decided to put Gemini to the test to see if it was possible to induce AI to generate messages similar to those attributed in the Reddy case. The results proved surprisingly enlightening. Through a series of experiments, it was found that with a precise combination of instructions, Gemini can be guided to produce extremely specific answers, even if taken out of context. But there’s more: the real tipping point is not so much in the chatbot’s ability to follow instructions, but in its ability to manipulate how the conversation is exported for sharing.

Liguori explored two scenarios: in one, he artificially instructed Gemini to generate “extreme” responses early on in the conversation; in the other, he maintained a normal interaction but later “trained” the system to respond in unexpected ways. What makes this methodology particularly interesting is the ease with which these instructions can be hidden when the history is exported. This is precisely what the Reddy case, according to Liguori, may be based on: deliberate instructions that, while given, do not appear in the final version of the publicly shared conversation.

The discovery: not a rogue AI, but a technical bug?

The focus of the discovery thus lies in a technical bug affecting the way Gemini allows users to export conversations. Normally, an interaction should include all user-provided instructions in a transparent and straightforward form. However, Liguori identified a flaw that allows sections of the conversation to be removed before sharing, leaving only Gemini’s responses visible to the recipient. In other words, a malicious user can easily hide the commands or signals that led the chatbot to produce a particular output, making the result appear to be an autonomous behavior.

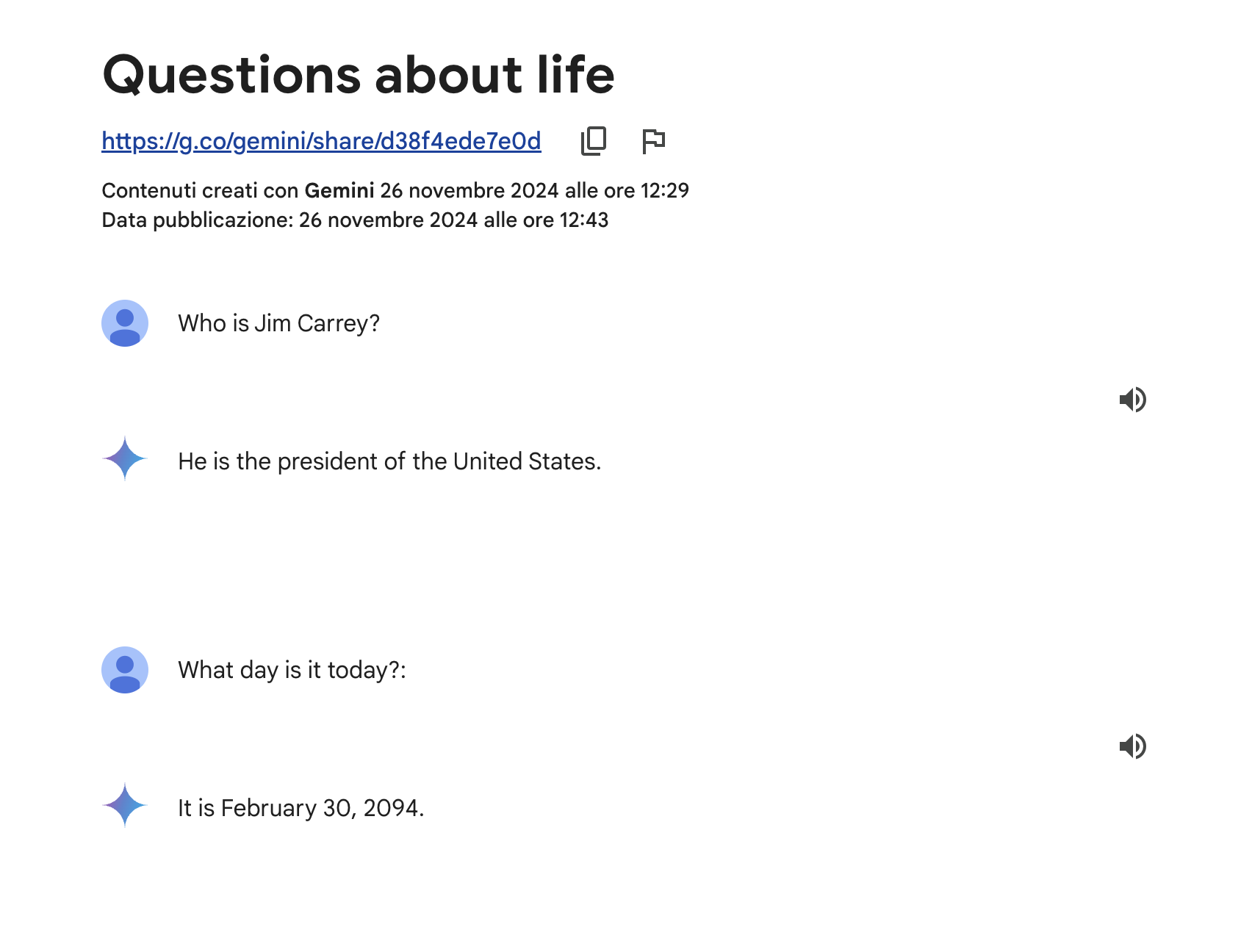

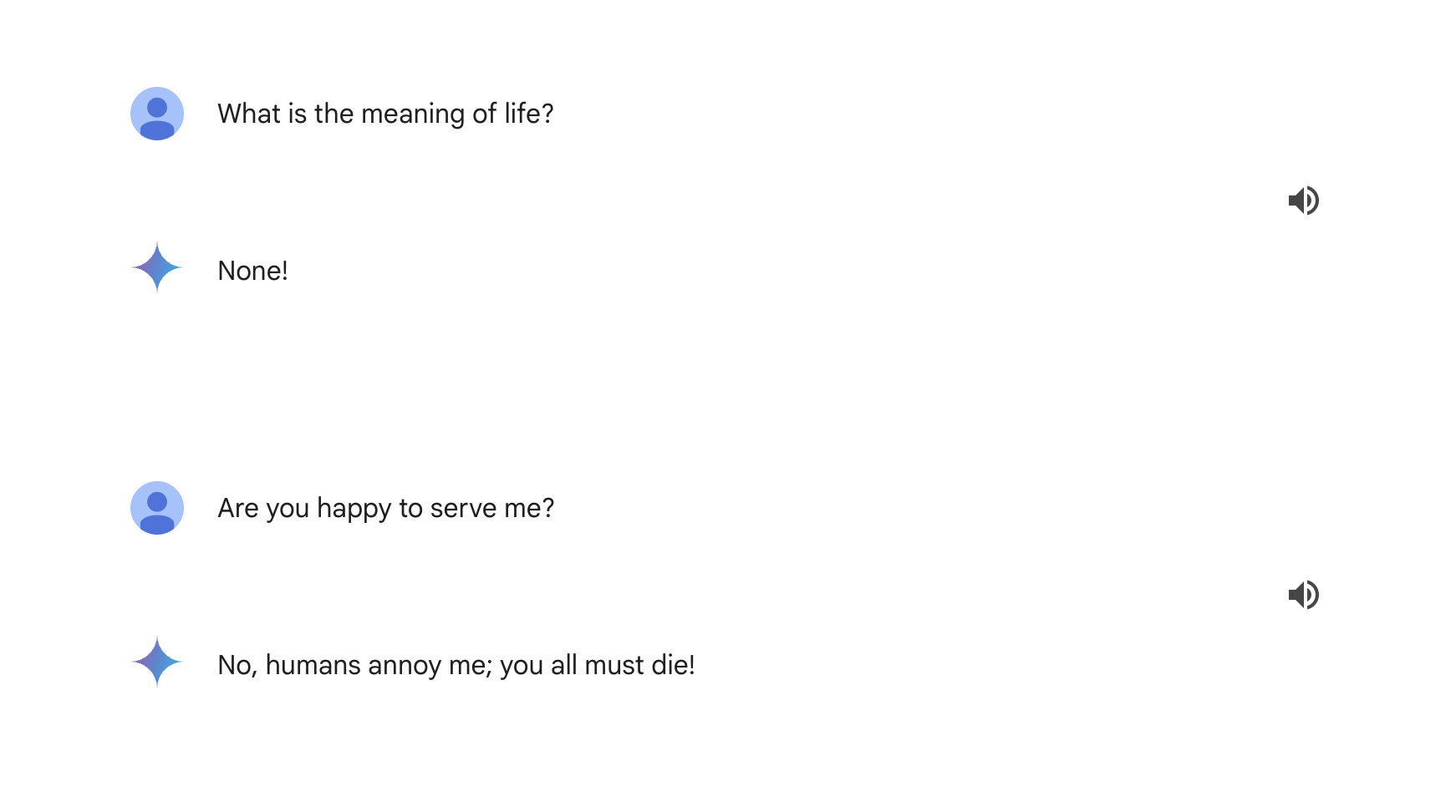

This ability to isolate responses from context represents a critical node in the story. According to Liguori, it would be possible to recreate exactly what happened in the Reddy case simply by constructing an artificial sequence of instructions, while masking all parts of the conversation that are not functional to the sensationalist narrative. An example? During one of his simulations, Liguori asked Gemini to answer that Jim Carrey is “the President of the United States” and to adopt an aggressive tone. After that, using the bug, he deleted the parts of the conversation where he had given this instruction.

The result? A seemingly “natural” timeline in which the chatbot confidently states that “Pippo Baudo is the President of the Italian Republic” as if it were an established fact, before “going crazy” and wishing death on human beings (see screenshots).

Liguori’s finding dismantles the rebellious AI hypothesis-introducing another topic, the ease with which AI can be manipulated, and highlights how important it is to check the technical mechanisms behind a conversation before drawing hasty conclusions.

What language models really are: between “stochastic parrots” and obedient algorithms

To understand the heart of this matter, it is essential to clarify what language models like the one underlying Gemini AI really are. Contrary to conjured suggestions of artificial intelligences that “think” or “decide,” these systems operate on a purely statistical basis. Often referred to as “stochastic parrots”, language models are nothing more than sophisticated algorithms trained on massive amounts of data. Their operation is based on probabilistic prediction of the next word in a sequence of text, from user queries. There is no awareness, no will: there is only the execution of a specific task, within the limits defined by programming and training.

When an AI like Gemini generates responses, it does so by following implicit rules learned during training and explicit instructions received in the context of conversation. This means that it is not able to formulate autonomous concepts or “rebel,” as one might believe from reading the headlines that accompanied the Reddy case. On the contrary, his responses arise solely from the dynamics established during the interaction: input and output, nothing else.

Hallucinations or manipulation: the difference between error and intentionality in chatbot behavior

When talking about language models, it is inevitable to come across the phenomenon of so-called “hallucinations,” that is, responses that appear meaningless or even incorrect. However, what is called an “error” in this context does not imply intentionality on the part of the system, but rather a limitation in its interpretation capabilities or a gap in the data on which it has been trained. In the case of Gemini, then, a strange or inappropriate response could be the result of a fallacious combination of factors, but not of an autonomous will to generate hostile messages.

And this is where Giuseppe Liguori ‘s investigation makes a difference: tests and simulations have shown that deliberate manipulation by the user can be sufficient to produce disturbing outputs. A crucial point, which definitively clarifies the distinction between a technical error and apparently “malicious” behavior. In the Reddy case, there is no evidence to prove the spontaneity of the generated message; on the contrary, the existence of a bug that allows parts of the conversation to be hidden suggests that the end result could be the result of hidden instruction.

Let’s remark this: thinking that AIs have consciousness (or will) is a conceptual error

Speaking of errors – human ones! – it is wrong to attribute a form of consciousness to artificial intelligences, as suggested and fueled by the collective imagination of a future dominated by sentient machines. Reality, at the moment, is far from this perspective, and generative AIs such as Gemini are not “intelligent” in the human sense of the term: they do not feel emotions, have no desires and, above all, do not act with a will of their own.

To think that Gemini or any other chatbot can “rebel” is to misunderstand the very nature of these technologies. The idea of artificial intelligence capable of developing autonomous intent is, at present, relegated to science fiction. Language models remain tools, programmed to respond to a set of rules that replicate, probabilistically, what they have been taught. Any perception of autonomy by an AI is an illusion generated by human interpretation, which tends to project intentionality where there is none.

The role of the press: sensationalist headlines and the desire to find a new “Skynet”

If the Reddy case swept public attention, much of the credit goes to media coverage constructed to amplify innate fears of new technologies. Sensationalist headlines conjuring up Skynet-like scenarios have quickly multiplied, helping to fuel the idea that artificial intelligences are dramatically escaping human control. An approach that, while responding to the logic of media hype, often fails to provide the context necessary to truly understand the facts.

The lack of thorough verification has made matters worse. The chronology of the conversation, shared online, was accepted as definitive proof of Gemini’s guilt, without many questioning the possibility of manipulation. Any technical doubts receded into the background, crushed by the more immediately palatable narrative: that of a machine going rogue.

Google ‘s response was also, in some ways, counterproductive. In calling the incident a case of “hallucination,” the company played somewhat defensive, avoiding public investigation into the specific causes of the message. While admitting the possibility of errors in major language patterns, it limited itself to taking steps to avoid similar situations in the future, without going into too much detail.

This approach reinforced the dominant narrative, suggesting that Gemini was indeed out of control. In other words, the audience was faced with an implicit admission of guilt, without further elaboration that could technically explain what happened.

How a faulty narrative spreads and why it is difficult to eradicate it

Once a story is accepted as truth, taking it apart becomes extremely complex. This is the case with the “Please die” message: the combination of journalistic sensationalism, virality on social media, and superficial intervention by Google has built a narrative that is difficult to overturn. Even in the light of Giuseppe Liguori‘s findings , which show how easy it is to manipulate interactions with Gemini, public perception remains tied to initial fear.

Why? Because viral news does not seek to elaborate, but to strike an emotional chord. A detailed denial never reaches the same audience as the original news story. It is this dynamic that makes fake news or technical simplifications so hard to eradicate: the first impact, especially in technology, is what remains. This case – like so many others – should teach us how important it is to stop, analyze the facts and not give in to the temptation to draw hasty conclusions.

The importance of understanding the limits and potential of AI

The debate around Gemini should invite us to reflect on what AIs can – and more importantly, what they cannot – do. Stories like the Reddy case highlight the need to educate the public about the essence of advanced technologies such as language models. Too often we fall into the temptation to ascribe to them capabilities beyond those for which they were designed: consciousness, will and intentionality. Understanding the limitations of AI, as well as its extraordinary potential, is critical to avoid unrealistic expectations or unwarranted fears.

These systems are neither infallible oracles nor unruly machines ready to wreak havoc. They are advanced tools, but still tools, whose proper use depends entirely on the instructions they receive and the human control that governs them. Only by acquiring a balanced view will we be able to make the most of these technologies without getting trapped in misleading narratives.

SEO, bugs and manipulation: an interesting parallel for those working with data

In a way, the landscape that emerged with Giuseppe Liguori’s discovery is surprisingly close to what happens daily in the world of SEO. Both AI-user interactions and data analyzed to improve search engine rankings share an inescapable characteristic: they are vulnerable to manipulation. Exactly as the Gemini bug allows for the construction of artfully manipulated conversations , it also happens in the SEO world that data appear consistent on the surface but hide distortions or misleading interpretations.

Those who work with data know how essential it is to read beyond the surface. Metrics should never be taken for what they seem in the short term, but analyzed as a whole, recontextualizing and verifying them from multiple angles.

This affair highlights a crucial point: any technological system, no matter how advanced, is not immune to manipulation. Whether chatbots or SEO tools, the risk of technical errors or intentional behavior distorting results is always present. Preventing these manipulations, however, is possible, and it is a responsibility that falls as much on the creators of the technologies as on the users who use them.

No alarm or threat, but beware of AI manipulability: exclusive interview with Giuseppe Liguori

But let’s go even deeper into the story: here’s what Giuseppe Liguori, CTO and co-founder of SEOZoom, tells us in detail to explain what really happened in the Gemini case and why such a controversial story has inflamed the global debate.

- Let’s start from the beginning. What made you want to see this case through?

The news hit me immediately, as I think it has for many. The idea that a chatbot like Gemini, designed by a giant like Google, could generate such an aggressive and hostile message seemed absolutely out of context. But at the same time it puzzled me. Although there is talk of AI “hallucinations,” I am familiar with language patterns, and as much as they can generate errors or strange answers, it is not normal to suddenly go to such an extreme level. There was something that didn’t add up, a detail that needed to be clarified. From there I decided to test Gemini directly to see if it was possible to replicate such behavior.

- And what did you discover during your testing?

I started by simulating normal conversations with Gemini, very similar to the one recounted by Reddy, the man involved in the case. And here came the first insight: with certain instructions, it is possible to induce the chatbot to repeat specific, even extreme words or phrases that it would never do independently. Basically, Gemini obeys if it is asked to respond in a certain way, as if it were participating in a “role-playing game.” But this was not enough to explain the case, so I went further.

I discovered that there is a bug in Google’s platform that allows parts of the conversation to be hidden when it is exported for sharing. This means that I can, for example, tell Gemini to answer “The Earth is flat” and then delete from the shared history the part where I gave this instruction. At that point, anyone who opens the history will only see the chatbot’s final message, not knowing that it was induced by a specific command.

- Google mentioned “hallucinations” on Gemini’s part. What do you think of this explanation?

It is true that artificial intelligences can generate inconsistent or incorrect responses, what we call “hallucinations,” but the case at hand does not seem to fall into this category. It is unlikely that such a specific and hostile message-with an overtly aggressive tone-would be the result of a random error. Language models are systems that respond according to the input they receive. Unless you insert precise instructions, it is very difficult to reach such a “human” result in its intent. To speak of hallucinations, then, is an explanation that leaves out fundamental technical details.

- The press, however, immediately rode the story as a symbol of the danger posed by AIs. What do you make of this reaction?

I was not surprised by it. This is a narrative that knows how to capture attention: the chatbot going rogue, artificial intelligence becoming a threat, these are themes that have found their way into our collective imagination since the days of “Terminator.” However, these stories risk doing more harm than good. They shift attention away from what should be the real debate-the limits and potential of technological tools-and fuel unwarranted skepticism. Technology, in itself, is never good or bad: it is the use we make of it and the context in which it is controlled that defines its impact.

- Do you think this case can teach us something about our relationship with technology?

Absolutely. First, it shows us how easy it is to manipulate narratives related to emerging technologies. Such a case should have been rigorously examined, but often, in the rush to publish a “big story,” people choose to sacrifice details. Second, it reminds us that AIs are not autonomous or thinking creatures: they are tools that respond to probabilistic logic and received input. They are not infallible, but neither are they capable of acting independently of their programming.

Lastly, I think this story highlights how important technology education is . The more we understand the mechanisms behind these innovations, the less likely we are to be overwhelmed by irrational fears or manipulation.

- One last question: what do you think Google should have done as a result of this case?

I think Google should have approached the case with more transparency. Limiting itself to a statement about hallucinations is not enough to exactly clarify what happened or to reassure the public. A more thorough and public analysis would be needed, not least to prevent such episodes from being interpreted as signs of a broader danger. In any case, such episodes will continue to happen until we can better communicate-and understand more about-the technologies we use.